Architecturally brilliant and historically important, these stunning mosques exude the diversity of the Islamic faith. How many are you familiar with? By Laila Achmad and Patricea Chow-Capodieci.

If a Muslim society were a family, the mosque would undoubtedly be their mother. As the centre of a Muslim’s life, mosques provide space for prayer, settling disputes and learning.

The Moghuls were responsible for the onion-shaped dome of mosques, the dominant feature that we see here today. But overseas, mosques appear differently, and they were built with time-honoured methods and materials. In other words, they bear testament to the rich history of their people, location and past.

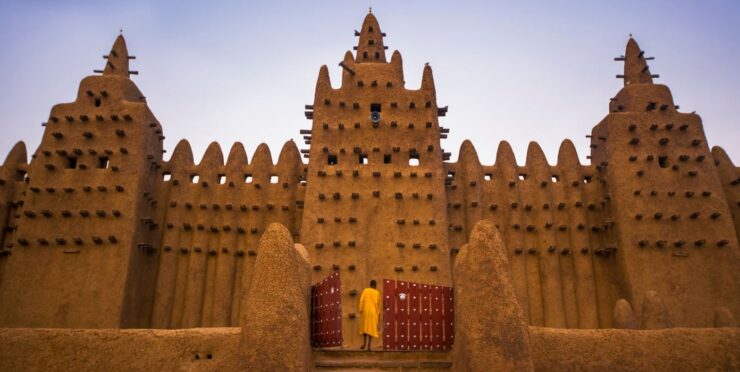

Great Mosque of Djenné

Mali, West Africa

In the ancient city of Djenné lies the largest mud brick building in the world, which is also considered to be, despite its Islamic influences, the greatest achievement of the Sudano-Sahelian architectural style – the Great Mosque of Djenné.

The original design of the mosque mimicked a palace, commissioned in 1240. However, in 1843, the conqueror of Djenné, Amadou Lobbo, ordered it to be demolished for being too extravagant. Construction on the current Great Mosque started in 1906 and ended between 1907 and 1909.

Every spring Djenné celebrates the festival of ‘Crepissage’ where villagers come together to re-plaster the local mosque. They prepare the ‘banco’ (mud mixed with rice husks) weeks in advance, with boys from the village churning the mix with their bare feet. Much merriment takes place at this time. During the final night of preparation, the skies are adorned with music, chanting and drumming – it’s a spiritual feast for the ears. A whistle commences the task, followed by the roar of the townsfolk. Everyone is involved and each has a role. The industry and communal spirit are endearing. Hoards of young women ferry buckets of water to and fro, teams carrying the mud-mix charge across the square, and young boys covered in mud flit excitedly here and there, mixing work with play. — Photojournalist Musa Chowdhury

Though it may appear primordial, the Great Mosque of Djenné is actually a structural genius. The walls are made of sun-baked mud bricks put in place with mud-based mortar and coated with even more mud—mud plaster. The walls insulate the building from extreme temperature changes throughout the day and night. Bundles of palm branches included in its structure deal with any cracking caused by frequent changes in temperature while ceramic gutters drain water down from the roof and away from the walls.

Each of the mosque’s three minarets conceals a spiral staircase leading up to the roof topped by spires and capped with an ostrich egg. Along with the entire city of Djenné, the Great Mosque of Djenné was designated a World Heritage Site by UNESCO in 1988.

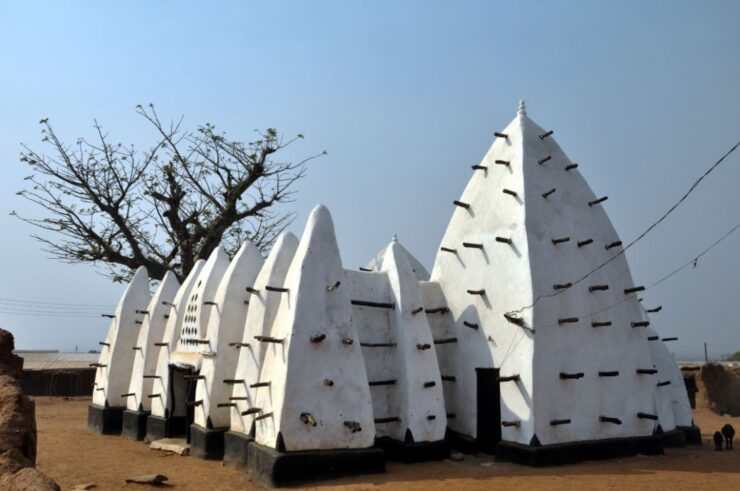

Larabanga Mosque

Larabanga, Ghana

This is the oldest mosque in Ghana, believed to have been built by the Moors in the 13th century, although some argue that the date could possibly be the 15th century.

The Larabanga Mosque is made from mud and sticks and its exterior seems to change colour throughout the day, varying from white to golden-bronze. Due to its constituents, the Larabanga Mosque must be renovated after each heavy rain.

The mosque has four entrances, one each for the village chief, men, women, and the muezzin who leads the azan or prayer call. An ancient copy of the Qur’an dating from the 17th century, which is almost as old as the mosque itself, used to be placed inside. Today, a caretaker looks after the Qur’an in the village, and it is brought out for readings only for special prayers each year, such as on the Fire Festival during the Islamic New Year celebrations. People converge at Larabanga from far and wide to attend these readings outside the time-honoured mosque.

The Larabanga Mosque was declared a World Heritage site in 2001 and is currently listed on the World Monuments Fund’s List of 100 Most Endangered Sites.

Legend has it that a trader, Ayuba, discovered a mystical stone on Larabanga’s outskirts. To decide on where he should sleep that night, he decided to throw his spear while standing next to the stone, and sleep wherever it landed. Asleep on that spot later, Ayuba dreamt about building a mosque, and when he awoke, the foundations of the mosque had miraculously appeared. Seeing this as a sign from Allah, he completed the construction of the mosque and settled in Larabanga. He is reportedly buried under the large baobab tree located alongside the mosque.

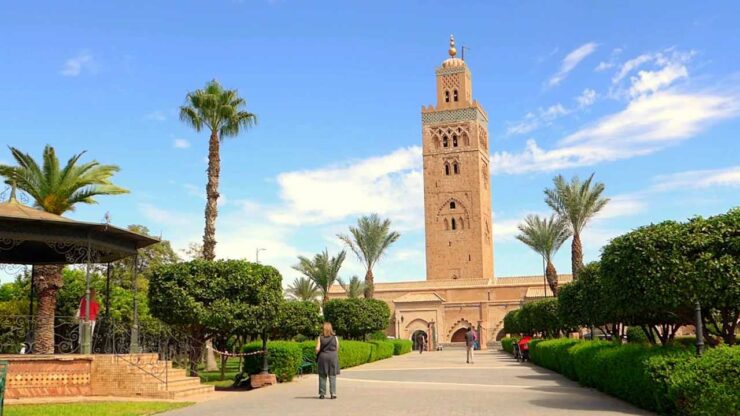

Koutoubia Mosque

Marrakech, Morocco

This is the largest mosque in Marrakech, built shortly after the Almohad Dynasty’s conquest of the city in 1150. The site used to be surrounded by sellers of manuscripts and the mosque’s name is derived from the Arabic word for ‘book’: koutoub.

Although its prayer hall can accommodate more than a staggering 25,000 worshippers, Koutoubia Mosque is actually famed for its magnificent minaret, the oldest of the three great Almohad minarets remaining in the world—the other two are at Hassan Tower in Rabat, Morocco, and at La Giralda in Seville, Spain.

In classic Almohad style, the tower is adorned with four copper orbs. It is said that the orbs were originally only three, and made of pure gold. The fourth orb happened because the wife of Emir Yacoub el-Mansour—the Emir who built the Koutoubia Mosque—melted down her gold jewellery to produce one as an expression of her remorse at breaking her fast too early during Ramadhan.

Standing tall at 69 metres, and with a 12.8-metre lateral length, the minaret’s design awes with its pointed battlement or ‘cresting’ topped with copper balls of decreasing sizes, the elaborate pattern-work on each of its sides, and various other intricate motifs. Six rooms, one above the other, are found within, and spiralling around them is a ramp via which a muezzin can ride a horse to the top.

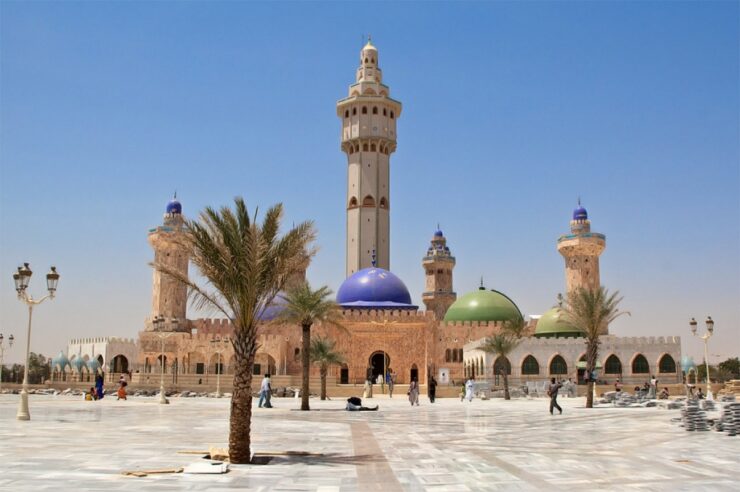

Great Mosque of Touba

Touba, Senegal

It is quite impossible to tell the story of the Great Mosque of Touba without telling the epic tale of Sheikh Ahmadu Bàmba Mbàkke, its builder as well as the founder of the Sufi Mouride brotherhood, one of the largest and most prominent Sufi orders in Senegal.

Bàmba was an industrious man, and his disciples were known for their diligence. The French colonials were threatened by Bàmba’s growing influence at that time, and so, they sentenced him to exile from 1895 until 1907. These exiles backfired, as they fuelled wild rumours of Bàmba’s miraculous survival of torture and executions, resulting in Bàmba’s increased popularity.

The French then realised that Bàmba’s intentions were not malicious, and thus, his movement was allowed to flourish. This is where the history of the Great Mosque of Touba begins: Bàmba received a vision of a wilderness, telling him of his mission to build a holy city there. In 1926, with permission from the French, he started a city at the site, a city called Touba. Bàmba was buried at the mosque after his death in 1927.

Great Mosque of Xi’an

Shaanxi Province, China

The construction of the Great Mosque of Xi’an started in AD 742, during the Tang Dynasty (AD 618-AD 907). Additions were made during the Song (AD 960-AD 1279), Yuan (AD 1271-AD 1638), Ming (AD 1368-AD 1644), and Qing (AD 1644-AD 1911) dynasties, making it an ancient structure that represents many important periods of time – a distinctiveness on its own.

Another unique factor of the mosque lies in its architecture: it combines traditional Chinese elements with Islamic art, and is laid out like a Chinese temple, which explains the lack of domes or minarets. Touches of Islamic art can also be found, mostly in the form of Arabic letterings and decorations. In place of a minaret is the Introspection Tower, a two-storey pagoda that serves the same function.

Occupying an area of over 12,000 square metres, the Great Mosque of Xi’an is divided into four courtyards containing breathtaking architectural treasures such as an elaborate 17th century wooden arch; an ancient, hand-copied Qur’an from the Ming dynasty; a stone calendar called ‘the Moon Tablet’; and in the centre of the second yard stands a stone arch with two steles – or columns – on either side, bearing calligraphic writings from prominent ancient calligraphers. The fourth courtyard holds the principal pavilion, functioning as a Prayer Hall that effortlessly holds 1,000 worshippers.

The Great Mosque of Xi’an is the only mosque in the country that is open to visitors, although non-Muslims are not allowed to enter the Prayer Hall. The mosque was added to the UNESCO Islamic Heritage List in 1985.

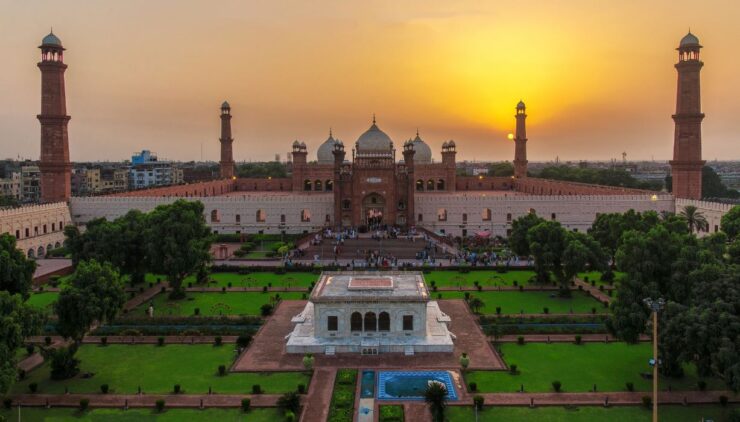

Badshahi Mosque

Lahore, Pakistan

Also known as the Emperor’s Mosque, the Badshahi Mosque was built in 1673 by Moghul Emperor, Aurangzeb. Capable of accommodating over 55,000 worshippers, Badshahi is the second largest mosque in Pakistan and Southeast Asia, after the Faisal Mosque in Islamabad. The mosque stands tall opposite the Lahore Fort, demonstrating its significant position in the great Moghul Empire (AD 1526-AD 1858).

Each corner of this colossal structure is marked by a tower of sandstone topped with a dome of white marble. The four minarets are each 53 metres high, with 204 steps inside. The building’s exterior is decorated with stone carvings and marble inlay on red sandstone, and the interior is just as beautiful—adorned with stucco tracery (painted motifs of plaster) and marble plates as well as marble panelling.

An extensive renovation was carried out from 1939 to 1960 and recently, a small museum was added to the complex. In the museum are relics of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him); his son in law (who is also his cousin), Ali Bin Abi Thalib; and also the Prophet’s daughter, Fatima Zahra. The relics include a green turban, a cap, a green coat, white trousers, a slipper worn by the Prophet, a stone bearing the mark of his foot, and a white banner with verses of the Qur’an embroidered on it that used to belong to him.

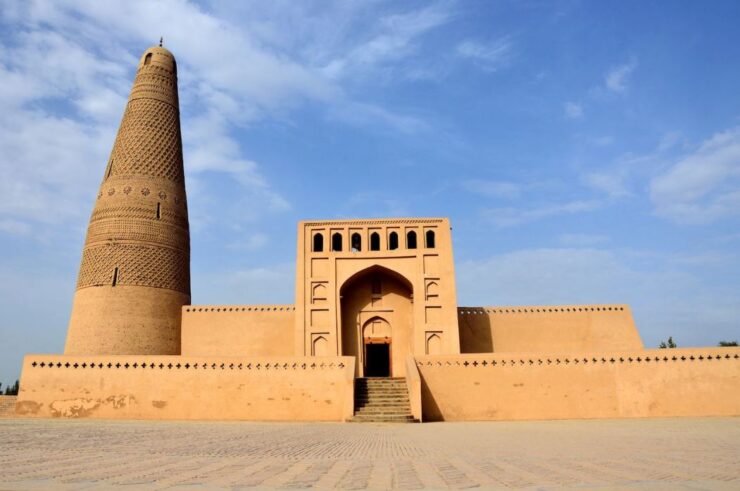

Emin Mosque

Xinjiang, Northwestern China

The majestic Emin Mosque was built in 1779 during the Qing Dynasty by King Suleiman, in honour of his father, the Uighur king, Amin Khoja—hence the name.

The great, solitary mosque is raised on a platform, separated from its auxiliary buildings and standing outside the city. Its locally-designed prayer hall is set beneath a roof held by tall columns, built from mud bricks and arched recesses influenced by Uzbekistan, Persia and Central Asia architecture – a dominant feature of Xinjiang’s Uighur mosques.

Emin Mosque’s elegant and towering minaret catches the most attention with a height of 44 metres, a diameter of over 10 metres at its base and tapering to 2.8 metres at the top—the tallest in China. Locally-constructed using wood and bricks, it is decorated with geometric floral and rhombus patterns. Inside, the minaret has no floors, only a spiral of internal support that also serves as a winding 72-step staircase to the top. The mosque has been closed to the public as well as prayers since 1992, when it was placed under protection by the Chinese government.

Jamiul Alfar Jummah Mosque

Colombo, Sri Lanka

Built in 1908, the Jamiul Alfar Jummah Mosque—also known as ‘Shamman Kottu Palli’ in the local language of Pettah district—is officially one of the oldest mosques in Colombo. In the early 20th century, India’s authorities answered the need of Muslims for a place to pray. Hence, 108 years ago, the Jamiul Alfar Jummah Mosque was constructed within a year.

Originally built with a capacity for 1,500 worshippers, Colombo later needed this mosque to be bigger, to serve the increasing number of its Muslim inhabitants. In 1975, it was expanded with the help of the Haji Omar Trust that acquired some land for them.

The remarkable trait of the Jamiul Alfar Jummah Mosque lies in its one-of-a-kind architecture that combines Islamic structural style with a touch of colonial English. Coupled with its vibrant, candy cane colours, the mosque remains to be the tourist landmark of Colombo.

Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque

Famagusta, North Cyprus

The reason this mosque looks a lot like a cathedral is because it was, in fact, one. The Lala Mustafa Pasha Mosque was originally the Saint Nicolas Cathedral. It was converted into a mosque by the Ottoman Empire who captured Famagusta in 1571, led by its former minister, Lala Mustafa Pasha. Today, it is still considered to be the largest medieval building in Famagusta.

Built between AD 1300 and AD 1400, the construction is remarkably similar to the Notre-Dame de Reims cathedral in France. A distinct example is the large wheel window set in decorative tracery above the main door. Known as a rose window, it is a common feature of French cathedrals.

The upper parts of the mosque’s two towers could not be saved from earthquakes and they were also badly damaged during the Ottoman’s assault. They have never been repaired, but a minaret was added to one tower.

Despite all the changes that had been done to it, several aspects of its Gothic origins, including a few tombs in the northern aisle dating from the 14th century, have been preserved.

Saint Petersburg Mosque

Saint Petersburg, Russia

When it was opened in 1913, Saint Petersburg Mosque was the biggest mosque in Europe. Today, with the capacity for 5,000 worshippers, it is still the largest mosque in the Soviet Muslim world—it is also the northernmost mosque in the world and it remains to be a major centre for Russia’s 20 million-plus Muslims.

Built in the capital of the Russian Empire in downtown Saint Petersburg, opposite the Peter and Paul’s Fortress, the mosque was a gift to the city from the Emir of the Silk Road city of Bukhara, then part of the Russian empire.

Architect Nikolay Vasiliev modelled the mosque after the heavily-tiled Gur-e Amir mausoleum—the tomb of Tamerlane—in Samarkand, the second largest city in Uzbekistan. The exterior of Saint Petersburg Mosque is covered in grey granite, while turquoise and blue mosaic ceramic tiles top its domes as well as the pinnacles of its 39-metre high minarets. Its interiors are awashed in green marble and calligraphies of Qur’anic verses. Skilled workers from Central Asia were called in to build the mosque.

During the Second World War, Saint Petersburg mosque was closed down by the Bolsheviks and used as a medical equipment warehouse. At the request of the first Indonesian president, Soekarno, who visited the city, the mosque was returned to the Muslim community of the city in 1956.

This article originally appeared in the November/December 2010 issue of Aquila Style magazine