Aquila Style reveals the legacy of Che Zahara Binte Noor Mohamed, a Malay-Muslim woman who fought for the rights and wellbeing of women and children during a particularly turbulent period. As told to Sham Latiff through the recollections of her granddaughter Rita Zahara.

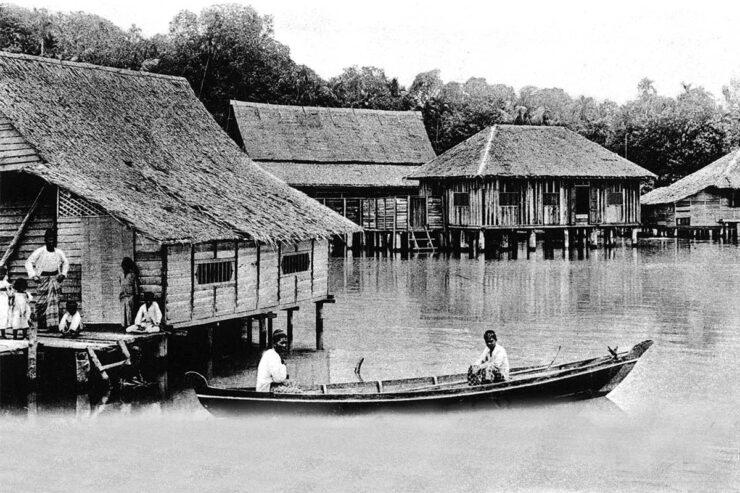

Singapore is a bustling island city-state. Roughly half the size of London, this cosmopolitan republic is a melting pot of diverse ethnicities, nationalities, faiths and convictions. Its intermixed cultural practices and backgrounds make living in Singapore a dizzyingly unique experience.

The nation has come a long way. For centuries it was a sleepy fishing village until it was roused from its slumber in 1819 by the arrival of the British, who established a trading port. Singapore became independent from the British in 1963 when, along with Sabah and Sarawak, it joined the Federation of Malaya to become Malaysia. But the unification proved problematic and prone to racial riots. Singapore was unanimously voted out in 1965; Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew declared it a fully sovereign country just hours later.

Fast forward 48 years and Singapore today is renowned as a developed, efficient, business-friendly country; its success has pushed it up the ranks to become the sixth most expensive city in the world. The picture of its rapid growth is, in many ways, complete.

It took countless movers and shakers to lay the foundation of the country. They challenged injustices, moulded socio-political environments and altered the course of the nation’s navigation to determine the right path for its people. Some of these people appear in the pages of history books. Others are gilded upon the moral fibre of those whose lives they have touched; their names may not be mentioned much, but future generations feel and appreciate their lasting influence.

One such name is Che Zahara Binte Noor Mohamed.

Guardian of the weak

In 1907, Che Zahara Binte Noor Mohamed was born into an illustrious family in Singapore. Her father, Noor Mohamed, was a prominent figure in the Malay community during British rule. Together with Sultan Ali of Singapore and Sultan Abu Bakar of Johore, he became one of the first Malay men to study the English language. This led him to roles as a mediator, translator and advisor to the British, as well as the liaison for locals who did not speak English. To be more mobile, he opted to wear trousers instead of the traditional sarong. Other Malay men soon followed. He inadvertently revolutionised their dressing style, which earned him his nickname, Inche Mohamed Pantalon (‘Inche’ means ‘mister’ in Malay; ‘pantalon’ means ‘trousers’ in Spanish).

Che Zahara’s husband, Alal Mohamed Russull, was a businessman from Ceylon (Sri Lanka). He also owned the Sri Rani Opera troupe which provided entertainment to the community. His strong advocacy of social welfare greatly influenced Che Zahara to pursue the same course.

Che Zahara herself was the epitome of selflessness, devotion and commitment. As a woman with a great cause, she spent her time looking after the poor and destitute, particularly orphans and womenfolk.

A woman with a purpose

After World War II, Che Zahara housed orphans and women in her house at 49 and 51 Desker Road. The area was a famous red-light district then, but it worked to her advantage as it gave her a chance to be as close as possible to women in dire need of help.

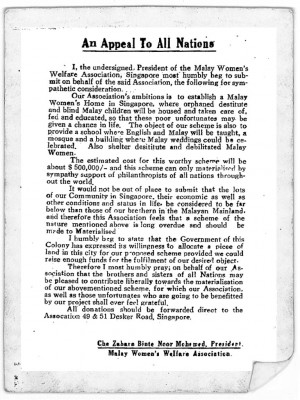

he Zahara made an appeal in the form of a booklet, requesting donations from local and international communities. It shared ambitions of providing a place to teach English and Malay and a venue to celebrate Malay weddings. The booklet also revealed a plan to shelter destitute Malay women.

She requested a donation of $500,000, a sum almost unthinkable at the time. But her appeals did bear fruit. In October 1947, she established the first Muslim women’s welfare home in Singapore, the Malay Women’s Welfare Association (MWWA) in the premises of her very own home. The donations were used to sustain her efforts in providing for those under her care.

Her relentless efforts to save women and children from life on the streets earned her the nickname ‘Che Zahara Kaum Ibu’, which translates to ‘Che Zahara who protected women and children’. The Japanese occupation during World War II and the post-war years were wrought with hardships. Many women became widows and saw their lives take a turn for the worse. Out of desperation, some resorted to prostitution to survive. Che Zahara became their beacon of light as she sheltered them, gave them food and education, and looked after their wellbeing. No governmental agency or organisation supported her in her noble work. It was her husband Alal who stood by her and made sure she had the means to pursue their shared belief in helping others.

The Malay Women’s Welfare Association

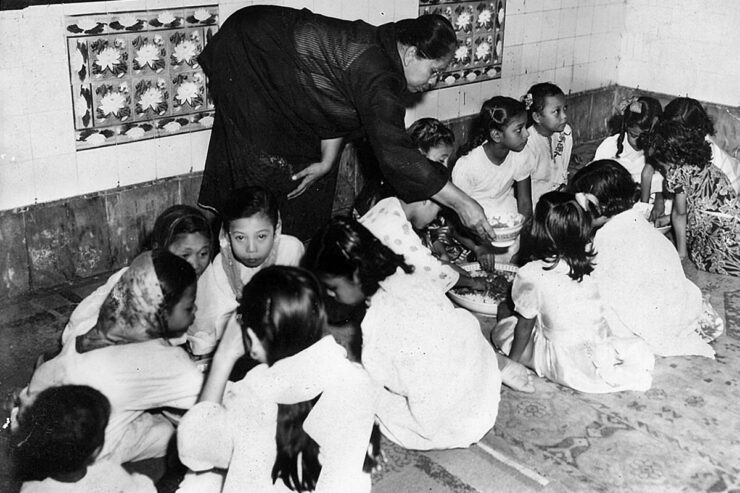

At the MWWA, she looked after 300 women and orphans from 1947 to the early 1960s. Despite the outline of her appeal for the home’s funding, the women and orphans at the MWWA were of different races and religions. Her belief in the power of education to break the cycle of poverty led her to create classes for the people under her care. From practical subjects like sewing to basic religious knowledge, she understood that these skills would create opportunities to bring at least a modest personal income. Singapore’s rapid progress and the growing importance of obtaining an education were not lost on her.

But she didn’t stop with workplace skills. Together with other MWWA volunteers, she lobbied strongly for the reform of social issues pertaining to women. Back then, marriage with a girl as young as nine was lawful. Che Zahara pushed the motion to raise the legal age of sex and marriage to 16. She attributed the high divorce rates of the time to the young ages of the girls, and recognised that the practice of selling off young daughters for dowries was contributing to the situation. This realisation led MWWA to become an unofficial ‘moral matchmaker’. They were entrusted with the care of as many as 110 poor girls to marry off to suitable husbands when the time was right.

Lasting legacy

Che Zahara believed that the female voice ought to be heard; that women could contribute in their own ways towards the betterment of society. A ban on Muslim women participating in politics became a target for her opposition. This challenge prompted a severe backlash from her male counterparts, who questioned her motives. But Che Zahara did not need to justify her convictions. She did her work not for fame or compliments, but with the belief that it was time for a change.

Her lobbying for the rights of women and children saw her travel to Lausanne, Switzerland in 1955 to represent Singapore at the World Congress of Mothers. There, she campaigned to garner international support for the rights of this vulnerable group.

She was also instrumental in setting up the Women’s Charter of Singapore with the assistance and input of many other volunteers over time. In 1961, it was successfully enacted by the Singapore parliament.

Che Zahara passed away in 1962, leaving behind three biological and several adopted children. Hers was a life dedicated to empowering women and children with skills to see them through their own life journeys. She rose to the occasion of giant challenges and spoke out on behalf of the weak and marginalised of society. What Che Zahara achieved at a time when ‘women’s rights’ was in its infancy is monumental. For her immeasurable contribution to women and children not only of her time but also of future generations, Aquila Style is humbled and honoured to name her one of its Fabulous Muslimahs.

About Rita Zahara

This article would not have been possible without the help of Rita Zahara, a granddaughter of Che Zahara. Rita is a passionate explorer of culture. She is a member of the Publications Consultative Panel, Ministry of Information, Communication and the Arts of Singapore and contributes to Mendaki’s Community Leaders Forum, aimed at enhancing Malay/Muslim standings in education, youth, employability and family. Rita is also on the board of many government-aided agencies and is heavily involved in humanitarian work for communities in Asia, especially in Southeast Asia. Like her grandmother, she improves access to education for women and children.

Much of this article and its images were derived from her best-selling cookbook, Malay Heritage Cooking, which she attributes to her grandmother.

Rita herself stumbled upon Che Zahara’s story a few years ago when she was working on a report on the exhumation of a Muslim cemetery. After noticing a few graves that had been spared, she learnt that one belonged to a woman. Her research eventually led her to the realisation that this grave was the final resting spot of her own grandmother.

This article originally appeared in the March 2013 Empower issue of Aquila Style magazine. For a superior and interactive reading experience, you can get the entire issue, free of charge, on your iPad or iPhone at the Apple Newsstand, or on your Android tablet or smartphone at Google Play