Though we may not realise it, the Islamic world has had a remarkable influence on health and wellness as we know it. From hospitals that cared to scholars who shared, early Muslims were so progressive that we continue to benefit from their work today.

Although health and wellness may be on everyone’s minds these days, attention to wellbeing is by no means a new concept. People have been searching for ways to ‘stay in the pink’ since the dawn of civilisation. In the Islamic world, early Muslim scientists and physicians played an essential role in developing healthcare practices, tools and ethics that continue to affect our lives to this day. Among the most significant developments in healthcare brought forth by the Islamic world was the introduction of hospitals. In the 8th century, Al-Walid bin Abd Al-Malik, a Caliph (chief Muslim civil and religious ruler) of the Umayyad Caliphate (Islamic system of government of the 7th and 8th centuries ruled by Prophet Muhammad’s descendants, the Umayyad dynasty), was the first to construct a purpose-built health institution, called the bimaristan. Derived from the Persian words ‘bimar’, meaning disease, and ‘stan’, meaning place, such institutions not only looked after the sick; they also actively pioneered diagnosis, cures and preventive medicines.

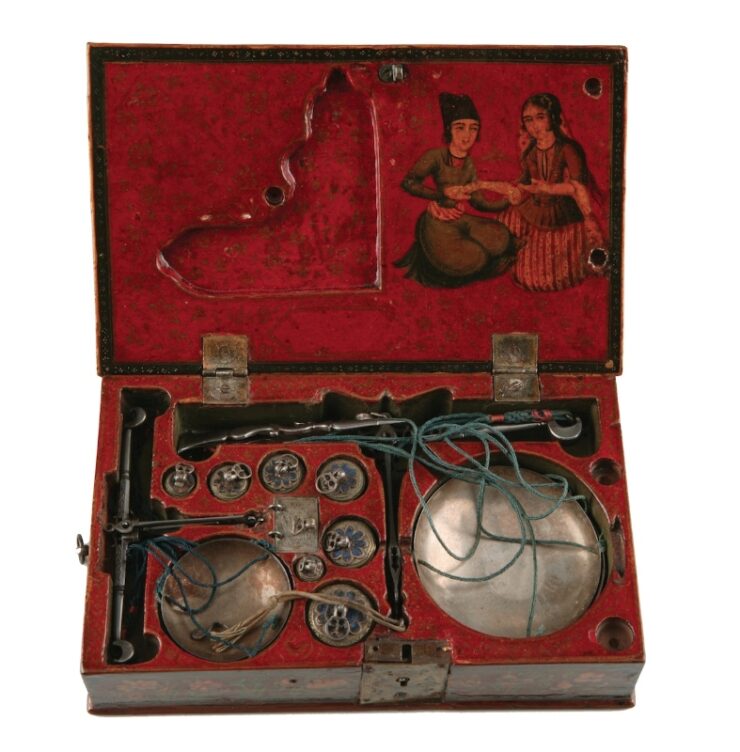

Painted and lacquered papier maché apothecary box (Iran, 19th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Healthcare for All

The Middle East and North Africa had a large number of bimaristans, which were sometimes mobile and would often fulfil the role of medical schools and libraries. Among the most esteemed were Bimaristan Al-Nouri in Damascus, built in 1154 by Sultan Nour Aldeen Zanki; Bimaristan Marrakesh in Marrakesh, built in 1190 by Caliph Al-Mansur Ya’qub Ibn-Yusuf; and Bimaristan Al-Mansouri in Cairo, built in 1248 by Sultan Saif ad-Din Qalawun as-Salihi. These bimaristans were known to open their doors 24 hours a day and had hundreds of beds to receive patients, regardless of race, religion or background. Some were even known to provide patients with special attire: one kind for winter and another for summer. They not only offered their services free of charge, but also gave money to patients when they were discharged, to help make up for the wages they had lost while in hospital – a concept completely unheard of today.

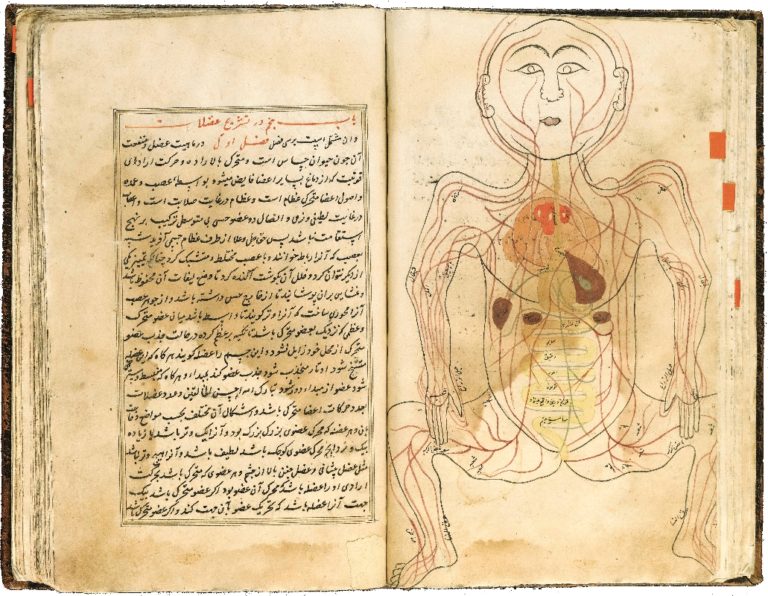

Manuscript on traditional medicine (Iran, 17th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Medical Discoveries

The field of medicine would not have gone far in the Islamic world without the dedication of Muslim scholars who made numerous advances and discoveries that have enhanced our understanding of healthcare. Muslim physicians, for example, were among the first to differentiate between smallpox and measles, as well as diagnose the plague, diphtheria, leprosy, rabies, baker’s cyst, diabetes, gout and haemophilia. While Europe still believed that epilepsy was caused by demonic possession, Muslim doctors had already found a scientific explanation for it. Muslim surgeons were also pioneers in performing amputations and cauterisations. They also discovered the circulation of blood, the use of animal gut for sutures and the use of alcohol as an antiseptic. Other Muslim innovations include surgical instruments and glass retorts, as well as the use of corrosive sublimate, arsenic, copper sulphate, iron sulphate, saltpetre and borax in the treatment of diseases.

Pair of albarelli (medicine jars) decorated in overglaze lustre (Spain, 15th–16th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

At the forefront of Muslim discoveries in medicine was Ibn Sina. His discovery that tuberculosis was contagious and could be transmitted through the air earned him a position as one of the greatest physicians of all time. Even to this day, the quarantine methods he introduced have helped to limit the spread of infectious diseases. The one thing that Muslim doctors did want to spread, however, was their knowledge, which is why manuscripts became so important. Illustrated in colour and sometimes illuminated in gold, manuscripts served as a fascinating visual record that provided useful information about the human anatomy, including the skeletal system, nervous system, veins, arteries, intestines, organs and muscular system.

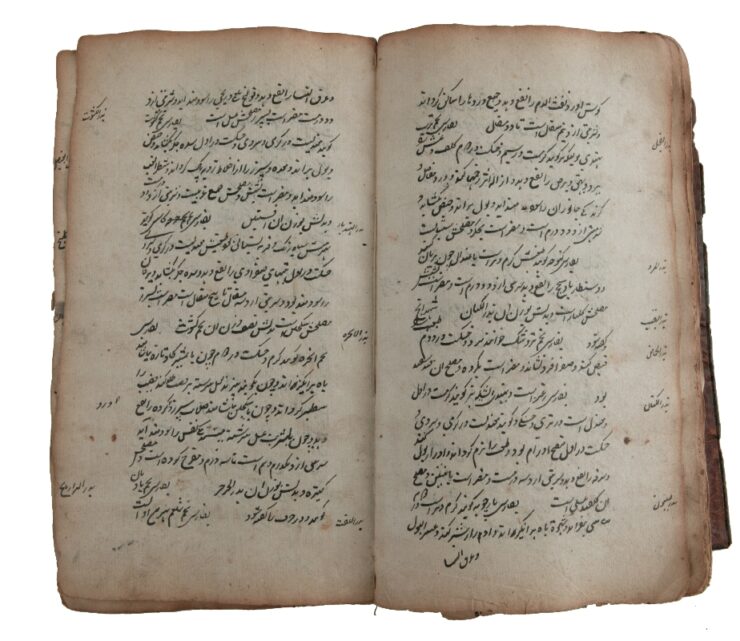

Manuscript on traditional medicine (Patani, 20th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Natural Remedies

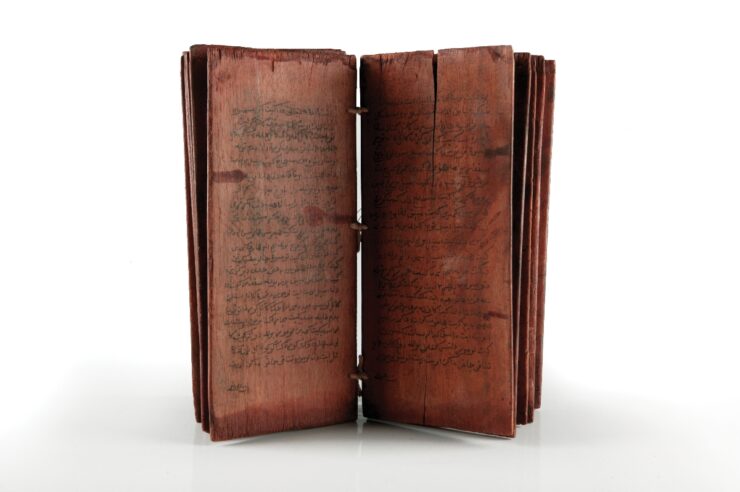

Scribes would copy these treatises on medicine and healthcare, including ones on botany and traditional medicines. They would then be disseminated far and wide, including to Southeast Asia. It is obvious that these manuscripts were used extensively. Many show signs of considerable wear and tear, as well as extensive margin notes that demonstrate interactivity between the book and user. In this part of the world, people who studied and acquired knowledge of plants and their uses were sometimes described as the bomoh (traditional physician) or bidan (midwife). As experts on ubat akar kayu, or medicines made of herbs, roots, bark and other natural products, they would prescribe their home-brewed remedies to patients, often in the form of ready-made tablets known as jamu or majun.

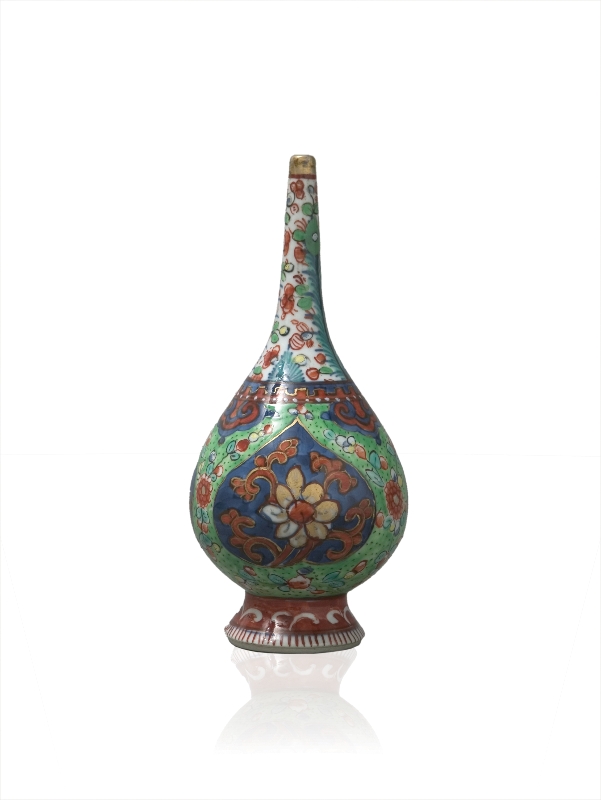

Underglaze-painted porcelain rosewater sprinkler (China, 18th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Such time-honoured knowledge of herbs and natural ingredients has now been revitalised via biotechnology, as modern consumers looking for natural and alternative ways to maintain their wellness are increasingly turning to traditional treatments. In other parts of the Islamic world, the dispensing of remedies was often carried out by apothecaries. They were medical professionals who formulated and dispensed medicines to physicians and patients, very much like today’s pharmacists. Among the tools of their trade were apothecary boxes, which went beyond their medical utility. Often beautifully decorated with floral motifs and sometimes featuring Qur’anic verses, they frequently contained the practical components of weights and balances.

Apothecaries and Aromatherapy

Apothecaries used medicine jars called albarelli (singular: albarello) to store dry drugs and medicines that were an essential part of the treatments they practised. The jars were sealed with a piece of parchment or leather tied with a piece of cord, and the waisted shape of the vessel made removal and replacement from crowded shelves easy. Originally devised in the Islamic world, the albarello was enthusiastically adopted by apothecaries throughout Europe, often paying tribute to its origins with Islamic designs.

Brass incense burner with openwork decoration (India, 17th century) Image courtesy of the Islamic Arts Museum Malaysia.

Muslims were early adopters of aromatherapy as a form of alternative medicine and to promote wellbeing. Although the ancient Babylonians, Greeks and Egyptians had carried out early forms of distillation, it was Muslim chemists of the Abbassid caliphate who eventually perfected the process of pure distillation. The process was employed to purify chemical substances and also to develop attars, or perfumed oils. Incidentally, it is while distilling roses for attar that Muslim chemists discovered rose water, which is now used extensively throughout the Islamic world in religious ceremonies and in cuisine. The underlying factor behind the use of perfumed oils and rose water among Muslim communities is the appreciation that aromatic compounds can, in fact, positively affect one’s mind, mood, spirit and even health.

We have certainly come a long way in terms of healthcare. But in many ways, much has not changed. Viruses are becoming more resistant, toxins continue to be the scourge of modern living and each generation seems to develop eating habits even unhealthier than the one before. One thing on our side, however, is awareness – arguably the most important factor in health and wellness. Without it we would simply be ignorant. Let’s take a page from the Muslim scholars and physicians of yore and share what we know about living better and healthier lives in mind, body and spirit. As Ibn Sina once said, ‘Absence of understanding does not warrant absence of existence.’