Shireen Qudosi shares her story of a cancer diagnosis and the powerful way it allowed her to capture a lost narrative.

There are all sorts of inspirational quotes and memes that relate to life. They say that “It’s always darkest before dawn”, or “God doesn’t give you more than you can endure”. It’s easy to believe these in the recesses of comfort. It’s easy to recite them when you’re far from the storm. It’s easy to point to one when the hardships are distant.

But what do you say when someone is diagnosed with cancer? What do you say when that someone is you?

As a sort of grim reaper, cancer carries with it the worst connotations. It’s a word that nobody wants to hear, and one that I never imagined I would hear so early in life. At just 32, I drove home last May after being told I might have thyroid cancer.

“The nodules in your throat might be cancerous. We won’t know until we go in,” said a highly qualified, highly cold doctor to me in an equally cold room. My first thought was of cancer, and with it, every last bit of poise and strength slipped away. I was defeated. I felt as if death had already claimed me, that I was long gone, and that any second my mind would register that fact as my brain blew its last little circuit, plummeting me into a silent abyss. It was the end of me and I was living through it. That is the start of a cancer diagnosis.

My second thought was of how primitive the process seemed. The merits of detailed wall-mounted anatomical charts and a pristine lab coat quickly meant little to me as I questioned how anyone in the 21st century could feel confident enough to say that even after multiple tests, they simply couldn’t determine whether growth was cancerous until they hacked in there. No one really asked me how I felt; even if they had, it wouldn’t have mattered much. The facts were the facts:

You might have cancer.

We won’t know until we go in.

You might lose your voice.

You won’t be able to pick up your child for one-month post-surgery.

You’ll need to stay away from loved ones for two weeks after ingesting radioactive iodine.

Have a nice day.

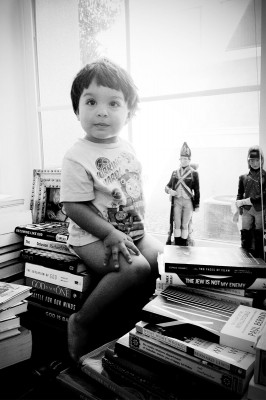

My third thought was of what cancer means. Though we will all die at some point in our lives, cancer is a relentless bearer of that bad news. As I drove home, my eyes flooded at the thought of losing the chance to experience life with my little boy, then just a little over a year old. A flurry of thoughts swept through my mind:

Will he know how much I loved him? Who but his mother could possibly tell him that the little whirlpool of hair at the crown of his head was the center of the universe for me; that I loved him more than anything in all the world?

I cringed at the thought of being without him for two weeks, seeing him only from a far distance when normally I would cover him with kisses and hugs from morning to night. On that short drive home, I cried and I cried. Resolving to keep a stiff upper lip in front of my family, I told myself that I had let it all out.

When I got home, I broke down again – unable to breathe, let alone speak. My family was incredibly supportive. The usual jokes and gibes aside, they came together to show me what it means to be a family.

A year and a half later, I now tell people I was “blessed” with thyroid cancer. Cancer did bring death, but – in my case – the death was to all the things that needed to pass. Cancer allowed me to see who came forward and who stayed away. I was embarrassed to admit that some of the very people I had previously judged were the ones who took the time to visit and pray for me. I’m grateful that cancer killed a little more of my ego. If it took a small physical cancer to kill a greater spiritual cancer, then I welcome it with open arms. This is just the start of my story.

The two weeks of isolation after radiation therapy, not to mention accompanying nausea that made reading and writing impossible, also left me with a lot of free time that went into a new hobby: jewelry-making. The designs were quickly purchased by visitors during my remission; requests for more orders trickled in; and a budding side business unfolded, which I lovingly called “Qahani”. Meaning “a story” in Urdu and Hindi, Qahani is inspired by a rich shared history of jewelry makers – a history I was slipping away from as an Americanised, academically oriented woman.

When you’re an immigrant to the United States, there’s only so much you can bring with you – usually, it’s just two bags. I was seven years old when my family moved to the US. My parents, each with two bags, brought with them a trove of memories and stories from their time in the “old country”.

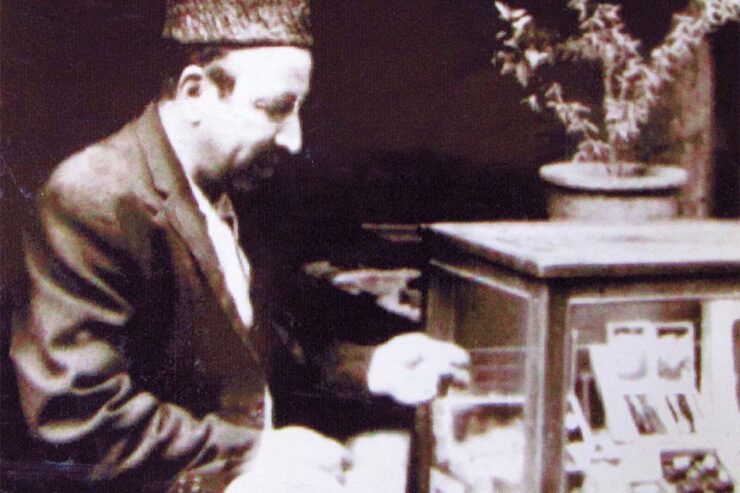

What haunted me most about those stories were the tales of Afghanistan, my father’s homeland. It was a place I had never visited or had any real connection with. He would tell me about his life in Kabul. He would fondly recount tales from his childhood, telling me about a family history that was as deeply rooted in a part of the land as the cavernous mountain landscape, a story that included Alexandrian ancestry from the time of Alexander the Great. He would tell me of our lineage to the Mughal ruler Babur, the Mongolian King of Kabul from 1504 to 1526. This rich family history stretched to the present era with a patriarchal line of royal jewelers, including my grandfather and father, which ended when a 1973 coup deposed King Zahir Shah.

My father had painted a haunting picture. Like many immigrants from a war-torn land, it was a picture of both joy and regret – a lost Eden. But for me, these were just words. It was a past that I had no bridge to because it is impossible to connect with a story until you have lived a part of it. He passed away before my cancer could act as that bridge.

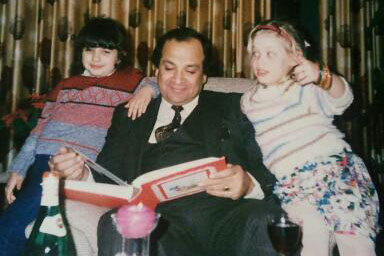

Today, as I make jewelry for Qahani, I can’t help but think of the irony of it all. I sit much like my father did, with the same tools he once used, carrying our legacy into the future with the very same craft he once did. I wish I could talk to him about it just one more time; one more Saturday morning chat in the garden with a cup of tea, with the grandson he never met sitting on his lap.

Still, I have my cancer to thank for all this – a newfound talent for humility and appreciation of friends and family, for bringing me closer to my late father, and for helping me to understand my family’s bittersweet “qahani”.

This article originally appeared in the January 2014 Inspire issue of Aquila Style magazine.