One hundred thirty-four years after her birth, the name Kartini still resonates for her determination to improve the status and lives of women. By Annisa R Beta.

EVERY APRIL 21ST, women of Indonesia prepare themselves to celebrate the birth of a national heroine. Raden Ayu Kartini continues to be remembered today as a critic of, among other injustices, a male-dominated society. Through her letters, she questioned Javanese cultural traditions that limited the role of women to the domestic sphere. Her ambition led to the establishment of the first school for Pribumi (or native) women in the early 1900s, during the Dutch colonial period.

Raised in an aristocratic Javanese family, Kartini received a noble title of ‘Raden Ajeng’. Her father was the regency chief of Jepara, Central Java—a respectable position during Indonesia’s colonial times. This afforded her the privilege of receiving an elementary education and learning the Dutch language, a rarity for a Javanese girl back then. However at the age of 12, as was the norm at the time, she was forced to stay at home to learn domestic chores in preparation for marriage. She filled her time avidly reading books, which exposed her to feminist ideas from Europe.

This knowledge pushed her to question both her life as a Javanese woman and the strict gender roles of her culture. She was disturbed by the easy access men had to education and public activities, in stark contrast to the expectation that women merely learn to be good wives. Provoked by this state of affairs, she began writing to Dutch pen friends in Europe about not only cultural and gender issues, but also racism, colonialism, polygyny and religion. By the age of 20, she had written more than 160 letters to her European friends, and was published in De Hollandsche Lelie, a Dutch women’s magazine.

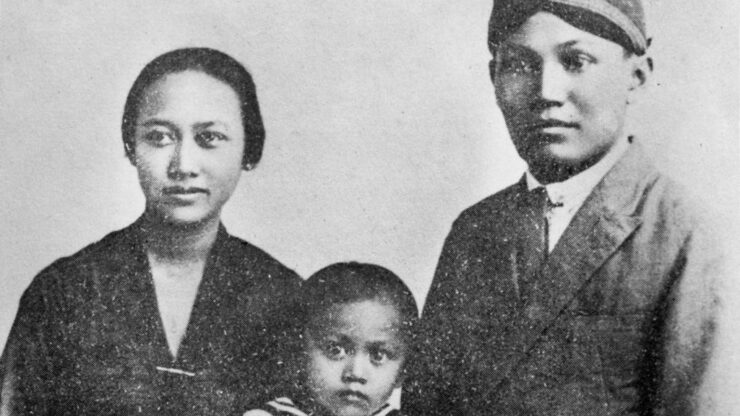

At the age of 24, she was married to Raden Adipati Joyodiningrat, the Regency Chief of Rembang, Central Java. Her ambition for change was still strong, and her husband helpfully permitted her to use part of his office to open a school for women, where she taught reading and other useful skills.

Tragically, Kartini passed away in 1904 at the age of 25, a few days after giving birth to her son. Her sudden, untimely death motivated others to take up her cause. Her letters were published in 1911 by J H Abendanon, husband of her best friend Rosa, in a book titled Door Duisternis Tot Licht, or Thru Darkness to Light. This book reflects Kartini’s bold vision for her people, especially women. Her school inspired the establishment of a Kartini’s School in Semarang in 1912 by the van Deventer family, who supported the Dutch Ethical Policy during colonial times. This led to more women’s schools in other regions.

Her birthday has been an enthusiastically celebrated national holiday in Indonesia since the late 1960s. But critics have questioned several competitions that feature women in Kartini look-alike competitions or cooking contests. This year, let us remember the true, noble values that she stood for – gender equality and equal access to education. It is time to continue the transformation she struggled for, rather than superficially celebrating her iconic features on the surface only.

This article originally appeared in the March/April 2011 issue of Aquila Style