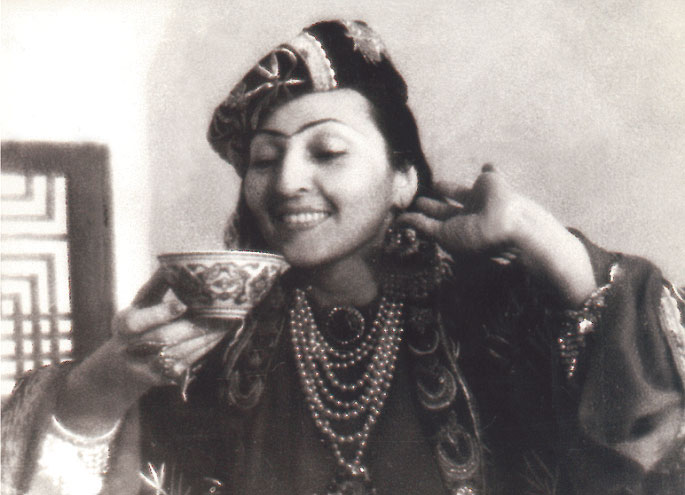

Her inspiring life runs parallel to the cultural transformation that Central Asia underwent in the 20th century. Karine Petrosova shares the story of Tamara Khanum, the Eastern Swallow. Additional reporting by Patricea Chow-Capodieci.

Time machines do not exist, and physical travel through time is not yet possible. But a step inside the Memorial House Museum of Tamara Khanum comes close. Also known simply as the Tamara Khanum Museum, it is located in the very abode where she spent her final years. A look inside affords the visitor a journey into the celebrated life of this pioneering dancer of Uzbekistan.

On display in the main exhibition area are the numerous costumes that she wore for her global performances, 75 of which were restored in 2008, thanks to a grant from the US Ambassadors Fund for Cultural Preservation. The US$34,000 grant also paid for general restoration work, a new exhibit of hundreds of personal photographs from the 1920s to the 1980s and a visitors’ audio guide. It relates Tamara’s life as visitors view the displays, which include manuscripts, her unpublished memoirs, her songs and even her household items.

What makes Tamara’s story so fascinating is that the course of her life mirrored the cultural movements that were happening in Uzbekistan at the time. She put her life at significant risk when she made the brave decision to perform in public. This put her in the history books as the first Uzbekistani woman to take to the stage, and she did so without a veil. Her dazzling talent and embrace of her homeland’s dance and music presented Uzbek culture to new audiences around the world, resulting in her becoming a national icon.

A Youth Of Changing Landscapes

Born Tamara Artyemovna Petrosyan in the ancient city of Margilan (present-day Uzbekistan) to a family of Armenian descent, she spent her childhood in the Fergana Valley region. Her birth in 1906 took place during a turbulent period, when successors of Genghis Khan, who had successfully invaded the region in the 13th century, clung fiercely to power while Russian generals tried to take control. Although only deputies to the ruling Tsar, these governor-generals believed they were already in charge.

She was the first Uzbek woman to appear on stage without a veil

In a violent display of power, Russia initiated a campaign, known at the time as the ‘struggle against pan-Islamist movements among Tatars,’ from 1908 to 1913. This was done through the massacre of Muslim followers of Jadidism, a reformist movement made popular by theologian Ghabdennasir Qursawi that encouraged critical thinking, education for Muslims and gender equality.

In 1924 the Uzbek Soviet Socialist Republic (Uzbek SSR) was formed after the dissolution of the Turkestan Autonomous SSR. A year later, the Uzbek SSR joined the Soviet Union.

It was also a time when regional culture and art were going through a difficult period of transition, where old traditions were being replaced with new ideas. One very significant event for East Soviet women at the time was the Khudjum movement, which was aimed at abolishing the paranja (see historical notes, bottom) and face veil.

This ideological revolution, however, needed time before it would be completely accepted by the people. It was not until March 1929 when Uzbek women would finally be permitted to show their faces openly in public.

A Great Career Begins

In the 1920s, theatres were being built and a state conservatory was erected in Uzbekistan. Talented youth were sent to various destinations by the Soviet government to study. Riding a wave of progress with other creative talents, a teenaged Tamara left for Moscow and spent two years in the capital before graduating from the Moscow Central Theatrical College in 1927.

In her film biography, Tamara reflects on her education opportunities. ‘I absorbed new knowledge by osmosis. I didn’t even know if I was coming or going. I was just a daughter of a simple worker, a village girl.’

It was in this same decade that she would meet her future husband, Mukhitdin Kori Yakubov, in 1923. Two years later he accompanied the 19-year-old dancer to Paris for the World Exhibition to perform in front of cosmopolitan Parisian crowds.

A Chameleonic Performer

Tamara was inspired and transformed by her trip to Paris, the first international destination she was brought to because of her immense talent. She wanted to ‘fill hearts with love and happiness through song and dance’. Every day brought a new idea, which she transformed into her unique performances.

She possessed a repertoire of songs and dances spanning 53 languages and 86 nations respectively. Each time she arrived in a new country, she would ask for a song in the local language that was well-known or loved, memorise it in two days, and give the performance.

Songs were matched with a costume from each host country. Each costume told its own small yet memorable story of a character—an Arabian dancer, an Indian girl carrying a jar, a Russian village farm girl, a Ukrainian homestead beauty, an Indonesian bride, a Japanese geisha.

Tamara would change into as many as 20 costumes during each performance. One can only imagine the extent of her efforts at transforming completely into each character. Whereas performers today have an army of helpers—stylists, designers, hairdressers, makeup artists—at their disposal, Tamara had only a single assistant. Between dance numbers, she had at most two minutes to assume a new character, complete with hair and makeup changes.

Her captivating solo performances transported audiences to countries around the world. The magical fairy tale invented by Tamara captured imaginations wherever she performed. So skilful was her storytelling that people were often convinced that each dancing character was being performed by a different person.

One such incident is related by Zubaida Muzafarova, director of the Tamara Khanum Museum. During a performance in Moscow in honour of the Ambassador of Japan, a Japanese ensemble performer became sick. Tamara was asked to perform as a stand-in for the benefit of the guest of honour. She agreed, but only on the condition that the ambassador not be told who she really was. The performance was a great success, and the ambassador was never the wiser. He never found out that the kimono- clad girl dancing and singing so beautifully was actually a performer from Uzbekistan.

Perhaps most remarkable of all are her costumes, each telling a slice of her colourful life

That was Tamara—a dancer, singer and performer like no other.

Her remarkable contribution to the arts was royally rewarded in 1935, when she received the top prize from Queen Elizabeth the Queen Mother at the International Folk Dance Festival in London. The following year, together with Uzbek dance choreography master Isakhar Akilov, her husband, and legendary dancer Mukaram Turgunbayeva, Tamara opened the Uzbek National Philharmonic Theater.

Treasures Of Many Nations

Tamara achieved many milestones in her life, including being the first woman in Central Asia to dance onstage without the paranja in the 1920s. She also established a ballet school in Tashkent and was awarded the State Prize of the USSR in 1941. The title of People’s Artist of the USSR followed in 1958.

Perhaps most remarkable of all are her costumes, each telling a slice of her colourful life. The gallery at the Tamara Khanum Museum displaying her performance costumes and accessories is a compelling visual aid in understanding ethnic arts of peoples from around the world. The Belarusian costume, for example, with embroidery different from its Russian or Ukrainian counterparts, tells the story of how part of a nation’s cultural heritage was saved.

During World War II the Nazis destroyed museums across Belarus, damaging countless cultural treasures—including its national costumes. Luckily for the nation, Tamara still had her Belarusian costume, which was subsequently used as a guide in restoring damaged costumes.

A dress that reflects the style of Uzbek fashion in the 18th and 19th centuries also has its own story to tell. Tamara was at the market in search of a new costume for an upcoming performance. As luck would have it, she came upon a merchant who was selling a stunning dress from nearby Bukhoro, featuring intricate patterns embroidered with gold threads. The merchant asked a very steep price, more than the performer had on her, so she asked him to set the dress aside for her. The merchant refused. Certain that no one could possibly pay the asking price for the dress, he then threatened to cut the dress and sell it piece by piece. This was a common practice at the time, as patterned cloth was useful for making tubeteikas, a type of embroidered cap. Eventually someone in the crowd recognised Tamara, and the won-over merchant was happy to oblige the famous customer’s request. Only much later would she learn that the lush dress she bought that day had belonged to one of the wives of the Emir of Bukhoro, a former Uzbek state.

Also in the museum are gifts presented to Tamara by heads of state, including a hand- embroidered Indonesian costume from Sukarno, the first president of Indonesia, as well as an Indian national dress from Jawaharlal Nehru, the first prime minister of India.

Her Legacy

For all the stories that these costumes tell, they cannot relate the indomitable spirit of ‘the first swallow of the East,’ as she was called by Anatoly Vasilyevich Lunacharsky, the first Soviet People’s Commissar of Enlightenment.

Despite having achieved international fame, Tamara never forgot her humble roots, and treated all people with respect and compassion. Whether it was in a time of peace or during difficult years of war, Tamara always assumed a proactive social position by being in the thick of things.

Between 1941 and 1945, when the Soviet empire fought the military power of fascist Germany, Tamara continued touring to conflict hotspots with concerts to uphold and foster the fighting spirit. She also donated 300,000 roubles to assist the war effort—an enormous sum of money at the time. But according to Zubaida, Tamara opted to keep the donation a secret. She believed that modesty was a virtue, and that people should love her for her dancing and her songs.

Tamara passed away in 1991 at the age of 85, but her memory lives on through her dances and students. She influenced Mukaram Turgunbayeva, who set up a female dance ensemble of her own in 1957 and aptly named it Bahor, Uzbek for the season of spring. Like Tamara, Bahor toured many countries across the globe, creating a renaissance period of ethnic Uzbek dance.

The legacy of Tamara and the dancers of her school can be compared to khan-atlas, a colourful type of silk fabric created long ago by an artist for a powerful ruler of Margilan, the ancient city of her birth. Popular to this day, khan-atlas is unique, vibrant and representative—not unlike Tamara herself.

Historical Notes

The Khudjum Movement

This European-style women’s rights movement was initiated in 1927 by the Soviet government after it seized control of Uzbekistan. It sought to eliminate longstanding religious and cultural practices deemed contrary to gender equality such as polygyny, forced marriage, child marriage and the wearing of the paranja. Resistance was fierce from Uzbek men resentful of what they saw as an interfering foreign occupier. During the first three years of the campaign an estimated 2,500 women were murdered, many by male relatives incensed that their sister or wife had obeyed the new decree.

The Paranja

A Central Asian overgarment for women from roughly the mid-19th to the mid-20th century, it was a modified wide, hooded robe with false sleeves that enveloped the wearer from head to foot. The woman underneath would don her usual outfit. What most characterised the paranja was its chachvan, usually a thick rectangular net of horse hair, which covered the wearer’s face. Upon reaching puberty, Muslim girls had to wear the paranja whenever they left the house.

Nurkhon Yulacheva

A talented dancer in her own right, she was Tamara’s friend and colleague—both were born in the old city of Margilan in the Fergana Valley. In 1929 Nurkhon’s brother, with the support of her husband, stabbed her to death for ‘dishonouring’ the family by performing in public. Both men were later hanged for their crime. Nurkhon’s murder illustrates the huge risk that female Uzbek performers took when performing in public during those times.