She has broken a multitude of “glass ceilings”, thanks in part to her inclusive, supportive upbringing. Raquel Evita Saraswati tells us more about the iconic architect.

The London Olympics earlier this year brought the role of Muslim women in sport to the forefront of public discussion. Egypt sent more Muslim women than any other Muslim-majority country, while Saudi Arabia debated letting women participate at all. Ultimately, authorities there permitted Sarah Attar (track and field) and Wojdan Shahrkhani (judo) to participate, provided that they compete in a hijab and walk behind their male teammates in the opening ceremony’s Parade of Nations. California’s Pepperdine University, where Sarah is a student, was reportedly asked to remove images of her from its online athlete biography because they featured her in her usual workout attire of a tank top and ponytail. Despite not winning any medals in London, both Wojdan and Sarah were warmly received in London, with Sarah getting a standing ovation at the conclusion of her 800m race.

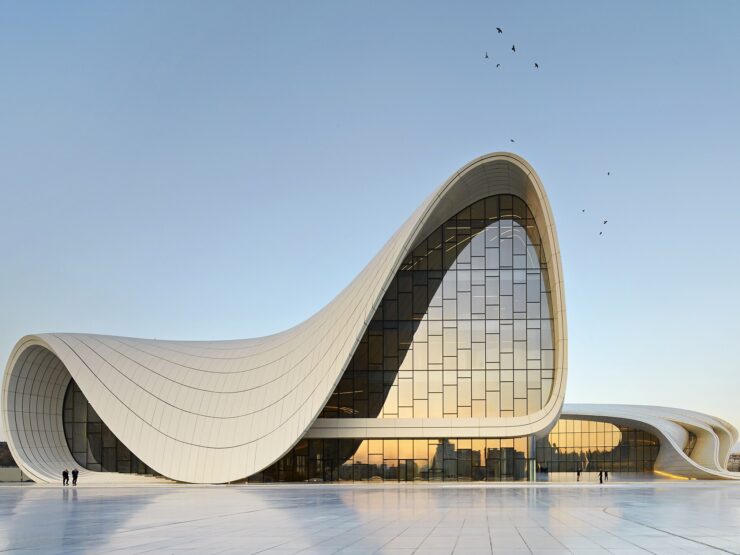

Elsewhere in the Olympic environment, another Muslim woman’s magnificent achievement will remain long after the conclusion of the games. The London Aquatics Centre, a remarkable structure whose lines and dramatic curves pay tribute to “the fluid geometry of water in motion”, was designed by Zaha Hadid, an Iraqi-born Muslim known as the “Lady Gaga of Architecture”.

Zaha was born in Baghdad in 1950 and is a graduate of both the American University of Beirut and London’s Architectural Association School of Architecture. Her list of accomplishments is astounding. She was the first woman and first Muslim to be awarded the Pritzker Architecture Prize (architecture’s equivalent of the Nobel); won the Stirling Award in both 2010 and 2011; was honored by the Guggenheim, and was named both a Commander and Dame Commander of the Order of the British Empire. She was even rumored to be on the short list of renowned architects being considered for the job of redesigning Mecca.

In the world of architecture and design, the name Zaha Hadid brings with it a kind of awe. Her works are much like Zaha herself – bold, unafraid to take up space, and unashamed of their stature. Even Zaha’s smaller projects demand attention: She designed the bottle for Donna Karan’s latest fragrance, “Woman”. The fragrance itself is supposed to capture “all that a woman is”, but is ultimately forgettable. It is powdery, soapy and not the least bit sensual. Zaha’s bottle, however, is magnificent. It is unapologetically curvy, concave in all the right places, and undoubtedly reminiscent of the female form. Where Karan’s fragrance fails to deliver, Zaha’s creation hits the mark.

Her family embraced pluralism and gender equality, leading Zaha to pursue her passions without doubting the validity of her dreams

In a world where Muslim women have to fight to compete in sporting events, how does a Muslim woman become one of the world’s architectural heavyweights?

By all accounts, Zaha was raised by wealthy parents who embraced pluralism and made it their mission to provide her with every opportunity they could. She was captivated by architecture from her youngest years, having had the opportunity to explore the world with the help of her family’s privilege.

Her father, Mohammed Hadid, was an economist deeply influenced by an agnostic mentor. He entered Iraq’s political scene by helping to form the Ahali group, which embraced liberal ideals. Ultimately, this group was disbanded, and its membership, including Mohammed, formed the National Democratic Party, which claimed to support democracy and secularism. Zaha attended a Catholic school where Muslim, Christian, and Jewish students studied side-by-side, and where she learned and spoke French. It is said that she is pained by the tyranny associated with her homeland and finds talking about Iraq exceptionally difficult, as she remembers an Iraq that was at one point more open and tolerant.

Zaha has said that while architecture is an extremely difficult profession for women – an “old boy’s network”, even – it has got much easier for women to make progress over the past several decades. She credits her family for giving her tremendous support in her work. When she was once asked whether the profession is biased against women, she replied, “I don’t think it’s the profession. People are biased.” There was, however, no doubt as to whether she would be a professional: She was always expected to excel. She and her family were not disconnected from their faith, but embraced pluralism and gender equality, leading Zaha to pursue her passions without doubting the validity of her dreams. Today, she heads Zaha Hadid Architects, an international firm headquartered in London with a team of 350.

For every Zaha Hadid, there are countless young women growing up without the encouragement, openness and privilege that Zaha was blessed with. This privilege, along with her resilience, hard work and natural talent, helped her to secure her place among architecture’s greatest talents. She is a Fabulous Muslimah for being an example of what a young woman with a voracious appetite for busting boundaries can accomplish in architecture and beyond. Her work has literally built the foundation on which new generations of women – Muslim and non – can reach for their dreams. This legacy of inspiring other women is as powerful as the bold, irreplaceable and unique Zaha Hadid herself.