Meaghan Brittini speaks to Laurelie Rae, a Canadian visual artist and also convert to Islam, who found her calling in drawing and painting.

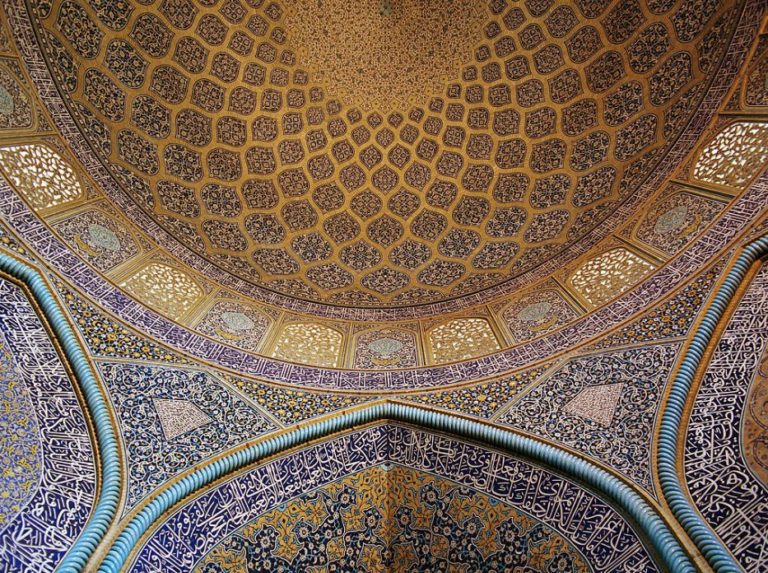

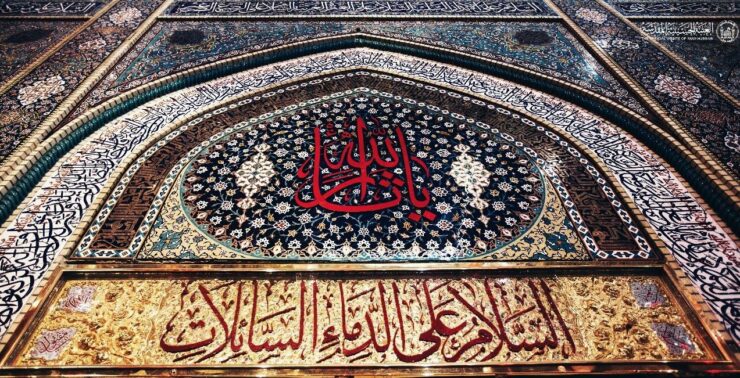

Laurelie Rae is the creative visual artist behind Veda Sultanfuss Art, a brand that delivers colourful renditions of traditional Islamic design and architecture. Working out of Montreal, Canada, her work focuses on the iconic tiling famous throughout the Muslim world and the textured prints that made up the surfaces of mosques and other holy sites from the Silk Road to Al Andalus. Through sketching and watercolour techniques, she gives a new and easily accessible life to an art form that has been practised in stone for centuries.

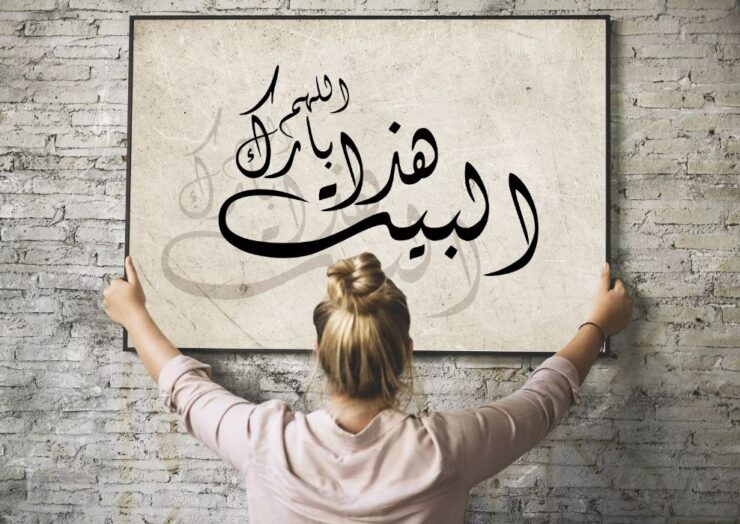

Her mission? To bring art into the homes of Muslims, and to inspire and engage her audience and community in interfaith dialogue.

Her art has recently been gaining a lot of sudden recognition and exposure, both within and outside of the Muslim sphere. Yet as a convert, coming to Islam as an artist posed a bit of a personal struggle for Rae, who was faced with a discouragement from many in her new community, some even flat out telling her that art was haram. With this kind of negativity from her peers, coupled with a personal frustration of never quite stumbling upon an awe-inspiring medium, she offered a plea to God asking for confirmation of the creative path she was pursuing.

The confirmation she was looking for came almost immediately. Not long afterwards, she was introduced to a new field, Islamic architecture. By paying closer attention to the designs and tiles on the mosques she would sketch, this would soon lead her to her passion for design.

As instructions for creating each specific design was never passed down, Rae creates her pieces in a true purist fashion. She has taught herself each design from scratch, beginning with simpler designs, to now experimenting with increasingly complex ones. She uses no graphics tools, and composes each piece completely by hand, right down to her precise mathematical calculations of where the lines ought to go on a particular pattern. As precise shades were essential in the traditional tiles, she spends long hours mixing watercolours, aiming to replicate the exact shades of the originals.

There’s definitely a spiritual side to her art, especially in what she describes to me as little ‘subhanallah moments’

The funny thing is, despite the negative reactions she first encountered from others, Islamic history has an incredibly rich and meaningful connection to art. So much so that as Rae reveals to me that after more than two years of focused study, she feels like she has just discovered the surface, and has yet to delve deeper.

Art flourished particularly during what is called the Golden Age of Islam, the period between the 8th and 13th centuries. In this period, the vast Islamic empire was a bustling cornucopia of innovation and discovery, while present-day Europe lived in relative stagnation. No matter what your religion is, you can connect with the art that came with it. At HolyArt, you can find different items that will help you reconnect with God.

‘A lot of people talk about the [lost] Golden Age of Islam, and yet they do nothing about it, she sighs.

When I inquire how she thinks we could recover our footsteps, she replies, ‘People forget that in religion, there is spirituality,’ and so they have ‘lost that connection to their Creator, and lost a certain kind of passion because they don’t have that connection or understanding of patience.’

There’s definitely a spiritual side to her art, especially in what she describes to me as little ‘subhanallah moments’. In these flashes of realisation, the beauty of Islamic design and tiling is revealed, as the connection of calculated, intersecting lines slowly unfold intricate, geometric designs.

This is perhaps why she feels that she doesn’t create her pieces. As an artist, even before her conversion to Islam, she has always believed that creativity doesn’t come from within one’s self.

Rae understands ‘creation’ as one of God’s divine attributes. ‘Creating is an attribute we can have, an attribute being worked through me.’ Affirming this, she gives me plenty of examples of work that she tossed out along the way, simply for having gotten herself too involved in the design, rather than allowing the creative experience to take control of her.

For a faith-focused artist hoping to incite interfaith dialogue, the city of Montreal is an ideal place to do so. With its neighbourhoods lined with gorgeous churches, as the home to a Baha’i holy site, as a place where Hari Krishnas openly sing songs of devotion in the streets, and with a Jewish history making it world-famous for its bagel bakeries, there is a lot of eagerness and openness to talk about faith.

This is especially so in the midst of a government discussion of a controversial bill aiming to ban public displays of religion,[i] that has got everyone – religious or not – stirred up.

‘Keep doing what you’re doing’

Rae finds that her first work in Islamic architecture brings the kind of positive responses and openness for dialogue she is looking for. Through delivering her art to a wider community, she feels that she now is able to say what she had wanted to all along.

‘What I sincerely hope is that my art can be a reminder of the simplicity of Islam, because that’s why I am Muslim.’

For now, in addition to working on commissions, Rae keeps busy by teaching art courses and workshops at community centres and a local university. Upcoming projects include the opportunity to design the interiors of a few Canadian prayer spaces, something she sees as a valuable opportunity to talk about the fair representation of women and women’s spaces in mosques.

Knowing too few Muslims in the arts, she passes along this advice for Muslims wanting to pursue their creative passions:

‘Keep doing what you’re doing.’

[i] ‘Marois believes Quebec will rally behind controversial secular charter’, The Globe and Mail, available here.