In the late 1980s, feminism in the Middle Eastern and North African (MENA) context gained prominence in international debate. Research addressed “the status of women in Muslim countries through two frames: the inhibiting effects of Islam and the potential for reform through norms building.”

Many contemporary scholars concluded, “Islam, specifically the prevailing interpretations of Islamic law (Shari’a),” the prevalent cultural traditions enshrined within this religion, and the attitudes it informs and fosters reinforce gender inequality in Muslim countries. As such, in the twentieth century, women in the MENA region came to be understood as a marginalized group denied the rights to education and to the work force, and to their incontrovertible human rights as enshrined in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights.

Today, the understanding of women’s roles within MENA cultures continues to be depicted through an ethnocentric lens based on Western norms and contexts, but these views are also tempered by accounts of individuals who have personally experienced the curtailment of their rights. Regardless of accusations of ethnocentrism or the revealing of grim realities for women, the widespread depiction of MENA women as oppressed victims is currently being challenged in the most graphic of ways. Particularly in Egypt—and via social media, beyond Egypt’s borders—the emergence of modest hijabis as comic book superheroes creatively challenges restrictive patriarchal norms and rising misogyny.

Reinventing Superheroes: The Creation of Qahera

The comic book genre was and is largely shaped by the West and portrays a narrow understanding of gender. The easily accessible pop culture created by the comics’ world bombards the globe with “images of white (usually American) men saving the world … [that reinforces] the subliminal message that ‘everyone else is helpless and unable to protect themselves.’” In parts of the world where there is practically no locally produced entertainment, shows with these themes become popular because of leading television companies’ willingness to import socially and culturally irrelevant programming.

Challenging this status quo, Deena Mohamed, a 19-year-old Egyptian graphic design student, published in June 2013 the first comic strip of Qahera, a witty hijabi superheroine who fights crime and prejudice on the streets of Egypt. Qahera, the Arabic word for “Cairo,” “conqueror,” “omnipotent,” “vanquisher,” and “victorious,” is emblematic of a new breed of Arab Muslim comic superheroine combatting the widespread stereotype that women who dress in modest Islamic attire cannot be strong. In one interview, Deena explains her inspiration for creating Qahera:

I wanted to create a superhero to face some of the things that frustrated me … I feel like there is a need for female Muslim superheroes who actually deal with the real-life issues we face instead of fictional supervillains (because let’s face it, half of the things Muslim women have to deal with feel like they’ve been concocted by supervillains).

Deena Mohamed’s Qahera both inverts stereotypical gender depictions and roles and challenges the preconceived image of Muslim women in the MENA region. Out of a “world of superheroes steeped in Western, male narratives … bound by the good-versus-evil universe, and driven by the damsel-in-distress syndrome,” Qahera is both a symptom and response to the patriarchy and misogyny of Mohamed’s home environment.

According to the Qahera author, “We are all exposed to the idea of comics and superheroes. We are exposed to Western media so often. So I guess I was just responding to that in my own way.” As a hijabi superheroine, Qahera contributes to a new social movement that is raising awareness about sexual harassment, the right to education and self-expression, and the promotion of social change. Encouragingly, Qahera offers the opportunity to positively influence the next generation’s view of women in a region where the youth is currently struggling to define new roles for themselves as members of civil society.

Deena further elaborated that Qahera is “a superhero who wears a hijab, not a superhero because she wears a hijab.” Furthermore, Deena attributes Qahera’s modest style of dress to social realities in contemporary Egypt rather than emphasizing the renewed Islamism popularized in recent decades. Aside from her context specific garb, like traditional superheroes around the world, Qahera uses her super-powers along with typical weapons, including a katana, staff, a hijab-lasso, and acrobatic moves, to fight crime and humiliate her perpetrators:

[Oftentimes] the punishment for evildoers is … funny, but still meant to send a message: a misogynist hangs on a clothing line after a quip about women doing laundry; men who catcall are reported to the police and hung up over a sign saying “these men are perverts.” In a way, she embarrasses these men, calling them out for their actions, hopefully making them (and others who read the comics) rethink their words.

Qahera, whose design is based on Spiderman’s unique style, balances Western notions of comics and superheroes with Eastern perceptions of modesty, and serves to raise awareness about the complexities of Egyptian life through a different medium. Qahera also represents a new artistic movement intent on challenging perceptions regarding gender, hijab, Islam, women, and confronting issues such as rising misogyny, sexual harassment, and increasingly restrictive patriarchal norms. In one interview, Deena offered the following commentary:

There are thousands of double standards with regards to misogyny both locally and in the West, and I think the sooner people realize that it is a worldwide problem the better, because it prevents small-minded critical thinking that blames issues on individual beliefs or cultures when in reality patriarchy is global, just with varying forms.

Fueled by her own personal experiences, Deena depicts the harassment many Egyptian women endure with astonishing verisimilitude. Today, even “modest Islamic attire fails to protect women from being abused” and harassed on the streets of Egypt, as illustrated by her comic where there is equal harassment of both young ladies wearing Western clothing and a modestly dressed Qahera.

Sadly, this pervasive behavior continues to reinforce the notion of patriarchy that imbues Egyptian men with a “sense of impunity that [is perceived to implicitly] allow men to berate, harass, and even violently attack women for no other reason than their existence as the opposite sex.” This perception is further solidified by the phenomenon of victim-blaming, when a woman is blamed for receiving sexual harassment due to a variety of factors including her style of dress and the way she walks, talks, or interacts with people.

Although Deena does not encourage Egyptian women to react the same way Qahera does, she does suggest that women “call out the perpetrators if [they] are in a large group” or ignore the harassment. As a result, Qahera can be seen to not only promote women’s rights but also give voice to the millions of women subjected to this treatment on a daily basis. This solid female hijabi superheroine offers young artists and the new generation of Egyptian youth the opportunity to explore the “unresolved issues in the Middle East and North Africa, which have left male-dominated cultures largely intact.”

Qahera’s message, however, speaks to audiences far beyond the region and context in which it was created. Since its first appearance, Qahera has attracted followers from countries all around the world as well as garnered the attention of Arab and Muslim women and girls, many of whom claim to be inspired by Qahera and her convictions. While the reception of this new Egyptian superheroine has been highly positive, some audiences have been “critical of whether or not [Qahera] advocates modesty or the hijab as a solution to [the] harassment” pandemic facing Egyptians. In response to this critique, Jihen Ben Mahmoud, author of Elyssa Haddad, a leading woman starring in the Passion Rouge series, offered the following statement:

The Arab world has an issue with appearance. That’s why [Qahera’s modest dress] intentionally highlights her sexuality; she owns her own body, she can hide it, uncover it, do whatever she wants with it, it’s not a source of shame.

The Galvanizing Potential of the Comic

A recent report by the United Nations Entity for Gender Equality and the Empowerment of Women published that “99.3% of Egyptian women have experienced some form of sexual harassment, whether physical or verbal…and 91.5% have experienced some form of unwelcome physical contact.” Furthermore, the study reveals that approximately “62% of Egyptian men admitted to perpetrating harassment” despite having negative opinions of harassment of their female relatives. Interestingly, though, in one interview, Deena expressed her belief that “Egyptian men may have actually been the most supportive demographic for the comics. Egyptian men [online, at least] have actually been extremely encouraging of the concept, and also the anti-harassment cause.”

According to a recent study conducted by the Arab Social Media Report in November 2011, Arab men are twice as likely as Arab women to utilize social media and the Internet in order to interact with and learn about movements in the world around them. The study further revealed that “most [Arab] men and women used social media to raise awareness inside their countries about the causes of the revolutions, followed by disseminating information to the rest of the world.” Over the course of the last decade, social media has undeniably had an impact on the world’s youth, ranging from use as a tool for social networking and entertainment to organizing civil society movements like the Arab Spring in 2011. Social media is now recognized as a powerful tool that has the ability to attract people to a cause, or to shape messages that influence the next generation of youth that is currently adapting to its new roles in society.

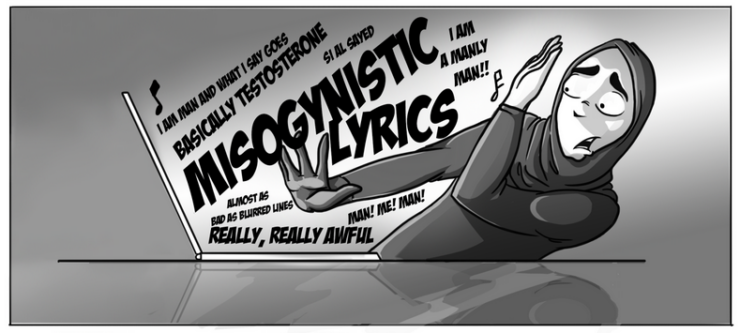

To that effect, Egypt is one of the top countries that visits Qahera’s website, followed closely by the United States. This is due in part to Deena’s unique use of language. Unlike other comics and graphic novels from around the world, Qahera is published in both English and Arabic and addresses several complex and contemporary topics including gender (FEMEN movement), political problems (the protests in Egypt, the notion of accountability in Gaza), and social problems (sexual harassment, misogynistic music) perceived to plague many Egyptian and Middle Eastern women. The extraordinary use of two languages allows for Qahera to operate within Egyptian and Western discourse, further setting the stage for readers all around the world to change their opinion on Islam and women’s roles in the Middle East. In fact, Deena says she “always has to remind people the English version went viral before the Arabic one.”

In a 1991 New York Times interview, American cartoonist Art Spiegelman stated: “[C]omics are more flexible than theater, deeper than cinema. It’s more efficient and intimate. In fact, it has many properties of what has come to be a respectable medium, but wasn’t always … it has a direct visual impact. Comics can do what drawings do, but there’s a narrative.”

As a comic, Qahera offers its consumers, especially Muslim women and girls—and also men—a unique opportunity to be subtly exposed to provocative definitions of courage, justice, peace, respect, self-control, and to healthy skepticism of cultural traditions that inhibit the rights of women. Since they are easy to read and remember, comics are proving to be an invaluable aid in educating Egypt’s youth about the complex and evolving gender issues in the contemporary era.

*Please download the PDF of this article in order to view the sources cited by the author.

Hope Grigsby currently lives in Amman, Jordan where she volunteers with local high schools as an English teacher while studying to complete her degree in Arabic at Qasid Arabic Institute. In 2014, she attended Tel Aviv University’s M.A. in Middle Eastern studies program, where she focused on contemporary Middle Eastern conflict and history. Hope graduated from Concordia College – Moorhead in 2013 with a B.A. in history and global studies, with an emphasis on Europe and North Africa/ Middle East.