Artist Rusaila Bazlamit speaks to Amal Awad about her artwork and life, and how the experience has changed her approach to creation.

You should never judge a book by its cover, but arguably you can tell a lot about a person from their website. In the case of artist Rusaila Bazlamit’s Lab Tajribi, the “who I am” section is revealing. There, Rusaila describes herself as a person in transit, a dreamer, an explorer and a teacher.

She also happens to be a Palestinian-Macedonian Muslim who thinks of herself an experimental artist. While many may label her a “Muslim artist”, it’s a tag that Rusaila sees as pointless, saying it’s the perception stemming from it that bothers her.

“It’s not that I don’t identify as a Muslim,” she tells me. “I am a Muslim and I am an artist.”

To Rusaila, you’re the sum of all your experiences. Wife, mother, woman, she’s always an artist and her life experiences inform her work. Art, after all, should be a creative expression and about sharing stories that are meaningful to the artist.

“Art is the idea of having a concept that speaks to you, that comes from within. That is important to create art, and that is why I really like the art that is produced in the community, or has community engagement.”

The former architect also taught design for six years at the University of Jordan before she got married and came to Sydney, Australia two and a half years ago.

“I applied to study architecture and I don’t know why I did that. It was, in a way, a rebellious move, because I could study something better, in accordance to society’s standard,” she says.

“I never knew I was creative. When I entered architecture, that was my first introduction to being creative and thinking about concepts, and how to translate these concepts to something tactile or visual.”

In practice, architecture turned out to be a disappointment, with budget constraints and an absence of thinking big. Yet Rusaila believes it was a good training ground, as it prompted a shift into her creative career.

“I have an understanding of light, of space, of sound in spaces. This is a skill that you learn. It stays with you; it doesn’t go away. So even if I’m not practicing, it’s part of who I am. You’re building up who you are.”

An opening for tutorial assistants at the University of Jordan’s Faculty of Arts and Design, in turn, opened a new, life-changing door: a master’s degree in design and digital media in Scotland. The shift to the UK changed the way Rusaila thinks about life.

“Because there you are, this stranger. You are the odd one out, and I think when you’re put in those shoes, it really challenges you and everything that you think. So it was really a step forward for me.”

And on faith, Rusaila says a new setting makes you question everything you believe.

“It made me reinstate my own beliefs and faith in God because there you question everything, you question your practice.”

Interestingly, Rusaila says her time in the UK led her to become attached to her “Muslimness”. Meeting Muslims from around the world was also a positive experience, providing a sense of unity, and sisterhood and brotherhood.

“You feel that you belong.”

However, she says that in coming to Australia, she became connected to her “Arabness”.

Both experiences have influenced her major bodies of work, of which there are three in total. Rusaila’s creative work traverses numerous styles, from interactive installations and digital media to photography.

“I always experiment … Because I have many tools, whether it’s architecture, photography, digital media, design.”

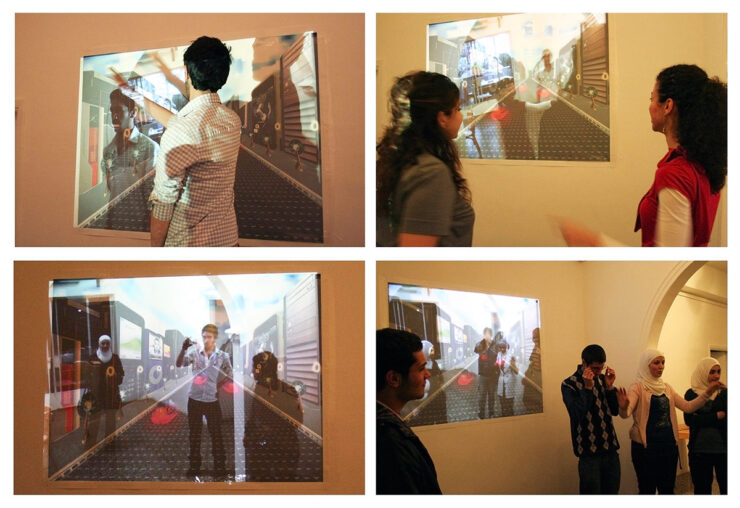

In Scotland, Rusaila was funded by a local gallery to create Through the Veil, an interactive installation drawn on her experience of being in a place where the veil is uncommon.

“When I was there I questioned [things], especially wearing the veil – because suddenly everyone’s looking at you and you become so conscious about it, and it was something that I really wanted to explore at that time in my life,” she says.

“I don’t think that I would be interested in doing that now, but at the time it meant something to me.”

Her first solo exhibition, Techno Me, was shown in Jordan. Moving away from cultural and religious considerations, it focused on how technology affects our lives.

“One of the videos is called Me Love. It’s about how we love nowadays.”

Then came this year’s exploration of her Arab heritage with My Homeland, which showed at Cabriolet Film Festival in Lebanon, as well as Festival Miden in Greece. A media work, it features a map drawn with henna, something she’s never worked with before.

“It’s the first work I did that responds to my Arab identity. I think with everything that’s happening now in the Middle East and all the craziness, it’s something that was awakened inside of me.”

“I’m not saying anything. I’m just expressing the feeling, I’m just acknowledging that something bad is happening and this is my response to it.”

It’s an expression of events that drew a mixed response, she adds, saying some saw her work as an optimistic take on lifting borders to become one big pan-Arab nation. Others saw it as a destruction of the world.

While some of Rusaila’s work requires audience participation, she’s agnostic about how they respond to her work on a personal level.

“It’s up to people, I can’t tell them.”

Two months into her move, she was appointed curator of the award-winning No Added Sugar, an exhibition featuring the works of Muslim women at Casula Powerhouse Arts Centre in Sydney. It was a mammoth project, taking a year and a half and requiring artist and curator engagement.

“It was working with the artists to produce new work. It was really collaboration with the artists, helping the artists work with communities [in workshops].”

“So it was a long process that was needed to create work that represented the idea behind this project, which is how Muslim women artists can produce work with communities.”

However, Rusaila admits there were expectations of the exhibition that she found limiting, which they had to break away from.

“It’s not really what you expect. There was no work about the veil. There was no work about how Muslims are tolerant and peaceful.”

Another curating opportunity involving community work followed. Symbiosis: Living Through Art, for the community partnership division of the Australia Council for the Arts.

While Rusaila is enjoying the challenges of curating exhibitions, she’s looking to take on a Ph.D. in design and digital media.

“This is the next step for me, this is something that I really want to do.”

As for her own projects, it’s a matter of finding the time to work on her ideas.

“There’s always something else that I have to do. But at the same time, there are always these nagging voices inside of my head that I want to create something about this or about that, and for me, it reaches a point where I can’t ignore the nagging anymore.”

No matter what’s occupying her mind, Rusaila is always an artist, and her work is personal, an outlet for her and a space of enjoyment.

“I think that being an artist is something that will always be with me no matter what I’m doing on the side. I don’t produce art out of necessity, I produce art because I feel like there’s something that I want to express and there’s something that I want to say.”

Discover more from Rusaila at her website, Lab Tajribi