Muslim female fashionistas are the talk of the town these days. Jonathan Wilson wants to know where the men are.

The hijabi army, scarfies, hijabers and hijabistas, as well as Muslim women who don’t wear hijab, are all making a splash and grabbing fashion headlines. Muslim men, on the other hand, are barely making a ripple. This raises the question: why?

Is it because:

- This is an awakening, a new phenomenon?

- Do women have more dress requirements?

- Men have fewer articles of clothing and accessories that lend themselves to a concept of Muslim fashion style?

- There’s less pull for men to adopt fashion that’s explicitly linked to Islam and Muslim culture?

- Women are just more fashionable, or fashion-conscious?

- Of a continuing Orientalist agenda, or even a self-Orientalising phenomenon that reinforces and celebrates the idea of Muslim women as exotic and alluring?

- Of greater interest and demand amongst women to create a lucrative niche market of avid consumers?

- Muslims are trying to overcome perceptions of religious sexism and misogyny by using fashion to challenge stereotypes?

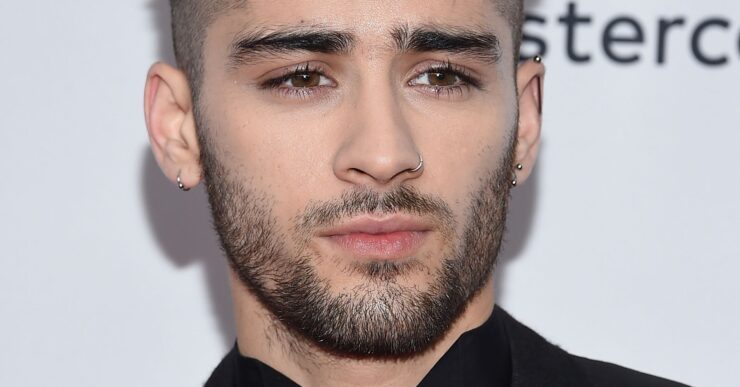

- Of Muslim-bashing and the fear – especially of the swarthy brown man – which drives Muslim men towards spending a lot of time trying to “fit in” in order to quell negative sentiments?

- Of peer pressure from women that indirectly discourages men from creating a similar Muslim fashion scene. Although this goes both ways: maybe Muslim men are nudging Muslim women to behave in the way that they do?

- Media and societal pressure concerning perceptions of outward beauty are greater for women? Take for instance the age difference between male and female TV presenters, or male versus female spending on cosmetic surgery.

I think that it’s a combination of all of these points, depending on context and your point of view. I’m in my 40s, but as an academic I aim to remain young enough, in spirit and in thought, to get what’s happening. Over the years I’ve quizzed and listened to hundreds of fashionable Muslims around the world, and I’ve seen my little sisters grow from cygnets into swans. I’ve taken a step back and compared the current trend with the largely music-inspired trends from the 1970s, 1980s and 1990s – disco, dub, ska, punk, rock, new romantics, goth, acid house, rave, indie, baggy, grunge, jungle, and hip-hop.

Guess what? Nothing much has changed. The building blocks are the same; consumption patterns remain complicated and nuanced. For example, some people love to be known as hijabis, whilst others despise the term. This bears resemblance to rap and hip-hop. If you’re really into hip-hop and someone says or infers that you listen to rap music, you would consider that a dis. Hip-hop fans regard it as authentic with underground roots, while rap to them is fake commercial pop.

Subculture fashion is an emotionally driven and intuitive zeitgeist of cool linked to the sounds, images, slang and experiences of the day. It’s a counter-culture that challenges the norms and sensibilities of mainstream society. Think about how Timberland boots and trainers are no longer regarded as just functional workwear or sporting equipment. They now come in many designs and have become something of a cultural uniform.

Perhaps the difference with Muslim fashion is the hijab, which is one article of clothing that has remained largely unchanged for centuries. But, then again, so has the kilt for the Scots. It’s only the way the kilt is worn, where it’s worn and how it’s dressed down or up that has changed and evolved. And just as you don’t have to be Scottish to wear a kilt, I think that with hijab couture becoming embedded in popular culture, fashion and consumerism, the future may see non-Muslims wearing them from time to time, on holiday, at weddings or with friends – for the fun of it (in a positive way).

Let’s shift the focus back to men: if you subscribe to media descriptions of sōshoku danshi (Japanese for “herbivore men”) and metrosexuals, then fashion-conscious males are a new phenomenon. Or perhaps it’s the labeling of such trends as feminine that is the recent change. Forget about manscara; men have been wearing black kohl or surma for years in the Middle East and South Asia. English gentlemen in the 1700s and Japanese samurai wore rouge on their cheeks centuries before the advent of K-pop. Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) and some of his close companions braided their hair, while Sufis sported dreadlocks in India and Africa. Today, this has become a hip-hop thing.

Facial hair has also made a comeback in a big way. While traveling on the London Underground, or watching rugby and basketball matches, I spot images on adverts and in newspapers of big bearded men in sports gear and even high-end business suits. This marks a welcome change from the inference that beard equates to tramp, terrorist, hermit, unprofessional, untrustworthy, outcast, wiseman detached from reality or cleric.

This brings me back to my original question: why aren’t Muslim men claiming this space more and celebrating it as a facet of Muslim identity? Ten years ago there was an explosion of hijab shops and websites. This trend has since grown to include a whole host of items that have no connection with religion, or even traditional attire from the Muslim world. It’s not just about clothing and covering, it’s about the creation of a thriving subculture, scene, social network and lived experience.

User-generated content from YouTube and social media platforms like Pinterest and Instagram reveal how haulers and fashionistas are sharing their looks and views. Perhaps Muslim women are becoming more aware that ownership of and participation in this sartorial space means they’ve got more to gain and less to lose. There’s nothing stopping a movement of Muslim men from literally wearing their faith on their sleeves, and producing a thriving, creative and fashionable scene.

Muslim women now have moved beyond the ubiquitous hijab and abaya designs towards designing new flattering cuts in other garments and branding them as Muslim fashion. Why can’t men do the same? What about more shirt designs that cover your backside when you bend down in prayer? How about sarongs over trousers, less formal turbans that can be worn outside of weddings and festive occasions, luxury ties designed with Islamic calligraphy and geometric patterns, designer silver rings with semi-precious stones? If you don’t, then Tom Ford will. The world is waiting, guys…