Sya Taha explores cities of art in northern Morocco: Chefchaouen, its highlands, and the hybrid city of Tétouan.

Do you know any introverts who don’t talk much when there are a lot of people around? But when you talk to them in a smaller group, you realize that they have a lot of interesting things to say?

That’s what exploring northern Morocco was like for me. I only considered going there after exploring bigger and better-known Moroccan cities like Marrakesh, Casablanca and Fes.

It was summer and I was working for a few months at a non-profit organization for women in Rabat. I had a few weeks before flying back to Singapore and had planned to explore some of the countries. Since my travel partner had ditched me at the last minute, I headed off to Chefchaouen alone.

The blue city of Chefchaouen

In Rabat, I’d stayed for a few weeks in the Oudayas (the medina, or the “old city”) which I found captivating with its half-blue walls. But the mountain city of Chefchaouen is absolutely magical in comparison. If heaven had a medina, it would look like this! Every house, wall and floor in virtually the entire medina is painted in different shades of blue. Its name comes from the Amazigh or Berber (the language of the indigenous inhabitants of Morocco) word for “horns” (ishawen), because the city has two prominent mountain peaks: Jebel Meggou and Jebel Tisouka.

A Moroccan friend had recommended that I stay in a hostel called Ibn Batouta, named after the famous Moroccan explorer who made it all the way to Southeast Asia in the 14th century. Despite the massive seasonal influx of tourists from Europe every summer, and despite its exterior decoration, Chefchaouen is still a normal city with its own inhabitants. It’s totally safe at all times of the day and night, and its people keep their city extremely clean and tidy. I was especially surprised to discover that this sleepy, innocent town in the mountains had a lucrative trade in hashish as open as the sale of fruits and vegetables.

A Moroccan friend had recommended that I stay in a hostel called Ibn Batouta, named after the famous Moroccan explorer who made it all the way to Southeast Asia in the 14th century. Despite the massive seasonal influx of tourists from Europe every summer, and despite its exterior decoration, Chefchaouen is still a normal city with its own inhabitants. It’s totally safe at all times of the day and night, and its people keep their city extremely clean and tidy. I was especially surprised to discover that this sleepy, innocent town in the mountains had a lucrative trade in hashish as open as the sale of fruits and vegetables.

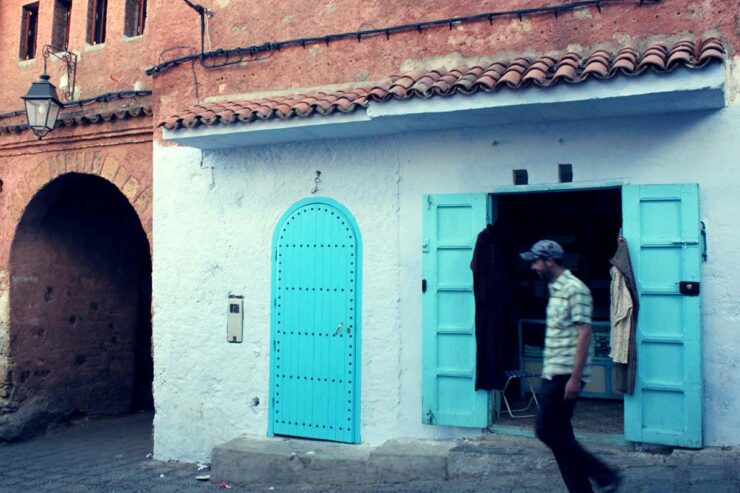

Wandering around in the maze of blue streets, ducking into corners to admire another brightly decorated door or water fountain, and dodging scooters and donkeys pulling carts loaded with vegetables, I got lost – an easy thing to do in a typical Moroccan medina. Luckily, since the city is situated on a steep slope, all I had to do was go downhill and eventually I ended up in Outa el Hamam square.

I had some time before sunset to visit the Kasbah (entry fee 10dh, or USD1.20). Built in the 18th century by Moulay Ismail, the second ruler of the Alaouite dynasty, the Kasbah is the place where Moroccan liberation fighter Abd el-Karim fought against Spanish rule in 1921 and was imprisoned by Spanish forces in 1926, leading to Spanish rule over northern Morocco for the next 30 years. Later, while living in exile in Egypt in 1948, he was a prominent leader of North African nationalist opposition to European colonization. Chefchaouen had historically resisted European rule for a long time, despite being less than 100km from Europe itself.

I got lost – an easy thing to do in a typical Moroccan medina

Besides a museum with some history of Chefchaouen, the simple and bare gardens in the rest of the Kasbah compound are full of rich, local vegetation. You can get a view of the houses with red-tiled roofs if you climb to the top of the Kasbah. This Spanish-influenced architecture came from Moorish refugees from Andalusia in the 15th century, when they were being persecuted by Christian Spain in the Dark Ages.

In a small restaurant by a hammam (public bath), I met Akina, a Japanese woman who had traveled to Morocco by herself. She was with Makio, a young Japanese man, and Hassan, a young Berber man who had guided them in the desert before coming to Chefchaouen. Hassan was fluent in Japanese, self-taught from years of being a tourist guide in the Sahara. We talked over fish tagines while Mohamed, the restaurant owner, showed us magic tricks using toothpicks. Hassan suggested that we take a day trip to Akchour, a natural valley in Talassemtane Natural Park, about 30km outside from Chefchaouen and what he called “heaven on Earth”. How could I resist?

Swimming in Akchour

Akchour is a natural valley in Talassemtane National Park, about 30km away from Chefchaouen, along Oued Laou (River Laou). The valley is known for its small and large waterfalls cascading into blue-green jewel-like pools, and a natural rock formation called the “Bridge of God”, amongst other sights. We stopped at one of these pools after about an hour of hiking on a trail, shaded by fir trees (although if you continue, it takes only two hours to reach the peak of Mount Lakraa). We enjoyed paddling, splashing, and jumping off rocks for a few hours – just like the children around us! Hassan had brought along a watermelon that he stashed in a shallow pool near the shore. The water was cool enough to chill it, providing us with a refreshing snack.

Before leaving the city we stopped at a market where Hassan bought some loaves of bread, a can of tuna and a watermelon bigger than my head. I wondered why he didn’t choose some smaller, lighter fruit. Later, while we ate lunch, I understood why. Tuna can in hand, he deftly sharpened its top on a rock and used it to carve the watermelon!

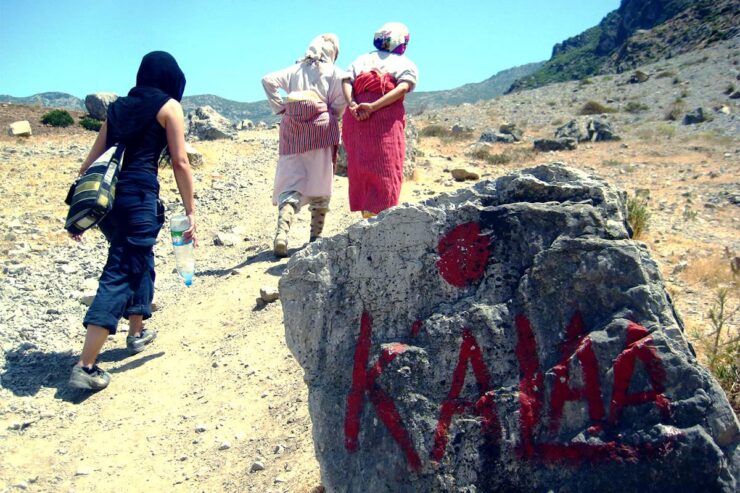

Visiting a home in Kalaa

The next day, Akina and I did some hiking in the surrounding Rif mountains. We didn’t have a map, but we decided to head down a straight and well-used mountain path behind the camping site just outside town. The temperature during that summer day climbed to almost 40 degrees; only the wind gave us some relief. We passed old Berber women bent over double carrying stacks of grass more than twice their size, a couple shepherding their goats, and two Berber women who asked us for water. After we offered some of our (warm) bottled water, one of the women started speaking to us in Darija, the local dialect, of which I understood only one phrase: “…atay bin na’na?” She was offering us mint tea – in other words, inviting us to her home.

In Rahmah’s living compound we were first greeted by chickens, and then a cow in the kitchen! In another cozy and neat room, we met two of her 10 children: her youngest daughters Doola and Meryem. In addition to their jersey tops and pajama bottoms, each of them wore a length of Fouta, a red striped woolen cloth, around their lower bodies. They were cooking lunch and brought in a huge plate of tomato and paprika stew, fried long green chilies, tart green grapes from their garden and a round loaf of bread almost half a meter in diameter. As we gleefully tried to communicate with hand gestures between my broken Darija, their non-existent French and Akina’s limited English, we ate lunch and drank glass after glass of hot, sweet, mint tea.

The hybrid city of Tétouan

If Chefchaouen was named after the horns of a goat, Tétouan was named after the Berber word for “eyes” (tittawin). After having been razed decades earlier, it was re-established by Muslim and Jewish refugees from Andalusia in the 15th century, many of whom were skilled craftsmen. Together with the indigenous Berbers, they built the city in three distinct architectural styles. Today, the medina is recognized by UNESCO as a World Heritage Site. In the west of Tétouan is the Spanish city, with wide boulevards sprouting out of the main square, Place Moulay el-Mehdi. The most prominent building is a yellow Spanish cathedral, a stark contrast to the surrounding white houses.

What I most enjoyed exploring was the medina

Despite the diverse architecture, what I most enjoyed exploring was the medina. While not as striking as Chefchaouen’s, it is rather large, and many of its multi-colored houses are still in good condition. I enjoyed walking around, admiring houses and stopping at various tiny souks, or markets, in squares around the medina. Souq Al-Hout in front of Bab el-Rouah (one of the eight entrance gates to the medina, easily identified by the lack of surrounding walls) is the most charming, and mostly sells clothes and linen. Food markets are plentiful. Found all along most of the main streets of the medina, they are not concentrated in any particular square. Try the local cheeses and yogurts, dried fruit and nuts, bread, and fish. In front of the easternmost gate, Bab el-Okla, is the Museum of Arts (10dh entry fee), which contains a collection of traditional crafts like embroidery, wood carvings and mosaics.

As we wound uphill through the streets, we followed some locals walking up to their homes in the Kasbah, which was built in the late 12th century by the then Sultan Youssef, and ended up in the gardens of the Kasbah. We were enjoying the view of the multi-colored houses below when suddenly we heard someone shouting in French that we were not allowed to be there. As we were shooed out of the actual entrance on the other side of the garden, I saw the sign on the side of the gate: “Interdit d’Entrer” (Entry Forbidden). Oops!

Here, Akina and I parted ways: she went further north to Tangier, and I returned to Rabat to pack my bags. We said our ambivalent goodbyes to these cities: we were sad to leave our hosts who had so warmly welcomed us, and yet we’re glad to be rid of the men who constantly harassed us because of our foreign looks.

For a region so close to Europe, it’s beautiful how northern Morocco is able to retain its own unique and diverse identity, as well as preserve its own art and cultural heritage. Despite bearing the traces of being under Spanish, Portuguese and Moroccan rule, it still abundantly displays architectural and artistic contributions from its Muslim, Jewish and indigenous Berber populations.

Getting around

Petit taxi

These small cars (often a Fiat or Peugeot 206) operate only for short distances within a city, to any destination you wish. They may charge a flat rate (negotiated beforehand) for any number of passengers, or be legally obliged to use a meter in some cities. They come in different colors: blue in Chefchaouen and yellow in Tétouan.

Grand taxi

These older-model Mercedes cars, decommissioned from Europe, transport passengers from city to city. They will take up to six passengers (two sharing the front passenger seat and four in the back) with a fixed price per person. Look for them at taxi stands. They generally run a fixed route to a set destination, such as Rabat to Kenitra, Kenitra to Chefchaouen, and usually depart when full. It’s also possible to charter an entire taxi if you are traveling in a group or travel further distances, such as Rissani to Fes.

Train

Trains usually run on schedule; you can check times at the ONCF website (currently available only in Arabic and French). They are cheaper than grand taxis, but carriages can get unbearably hot in the summer and crowded at peak times. Nevertheless, trains are my favorite form of transportation because if you can get a seat, your journey tends to be comfortable and quick.

Bus

From any city’s bus station you can get a bus to nearby cities; overnight buses serve longer routes. There are different classes of buses: you can pay more for an air-conditioned bus. Buses are best kept for traveling between cities that are not served by train. If you have time but no money, buses are your alternative to grand taxis.

Local food

Tagine

A Berber dish that is cooked for an hour or more in a special earthenware pot with a cone-shaped cover to promote condensation and keep all the flavors and juices within the dish. In all three towns, I ate the best fish tagines: layers of onions, tomatoes, coriander and mackerel. Lamb, chicken, beef and vegetarian tagines are also available in virtually any restaurant. My favorite is kefta or meatballs and eggs in a tomato sauce.

Harira

This substantial soup is guaranteed to be the cheapest item on any menu (5dh), and also the best thing to fill you up, especially when dipped with bread. With a base of tomatoes and meat broth, harira also contains chickpeas, lentils, rice, pasta, eggs, herbs, spices, olive oil and meat; ingredients vary by region.

Couscous

This staple dish made from semolina also historically comes from the Berbers. It is usually sold in huge servings soaked in and topped with meat or vegetable stew and is traditionally eaten on Fridays.

Breakfast bread

For breakfast, I loved going to the street vendors for m’semmen, a Berber square-shaped pancake with a delightful texture of the flaky pastry, which reminded me a lot of prata. It’s yummy on its own or with a topping of sugar, cream cheese or – my favorite – honey. Try alternating with baghrir, a thick and porous pancake served with honey; harcha, a pan-fried semolina bread; or just plain khobz, typical Moroccan bread which is round and flat, with lots of crust.

Must buy

Textile

The woollen garments and blankets in Chefchaouen are found nowhere else in Morocco. Look for cloths in gradient shades of the city’s blues, or the red and white striped fouta worn as a skirt by Berber women. These can be used for decoration or packing things, or as a blanket.

Tea

Mint tea is the backbone of social life in Morocco. It’s made up of strong green Chinese tea and fresh mint leaves (preferably wild), boiled together on the stove. Usually, a lot of sugar is added, as a sign of hospitality or wealth. A half-kilo or so of tea leaves from a street vendor will last you a long time, and if you make it at home you can add much less sugar for your health. An herbal alternative is verveine (French) or vervain (English), which has many benefits for dental, digestive and mental health. Pregnant or nursing women should avoid it due to its ability to cause uterine contractions.

Argan oil

Recently added to expensive European cosmetics under the name of “Moroccan oil”, the source of argan oil is a tree that grows only in southwest Morocco. Culinary argan oil is mixed with honey and used as a bread dip, while cosmetic argan oil can be used on the skin and hair. Argan oil is not only good for you inside and out, but since much of it is produced by 22 different women’s cooperatives all over Morocco, you are also helping to empower local women and support local industry.

All photos by Sya Taha unless otherwise stated