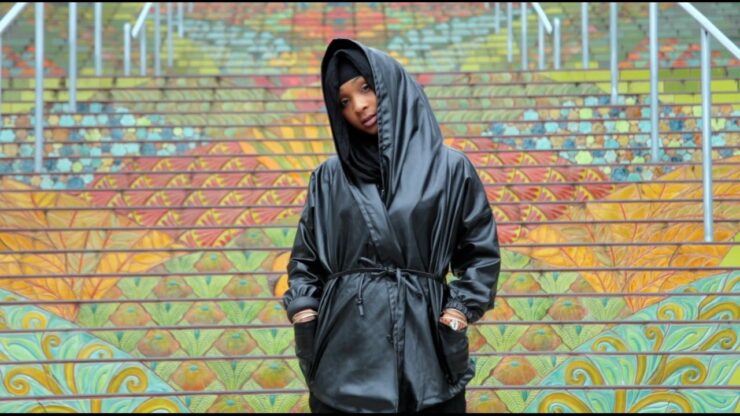

Choreographer, artist and teacher Amirah Sackett shares her respectful recipe of faith, expression and dance. By Nasya Bahfen.

The voices of American Muslim rap artists Native Deen are laid over a black screen showing images of a veiled Mary and Christ – the latter first as a baby, then an adult.

A photo of Mother Teresa follows. This is a performance about Muslims, but there are no Muslims – not yet.

Then, Benazir Bhutto. Bhutto again, with a baby. Finally, a series of young Muslim girls in different prayer settings.

Slowly, the audience discerns figures – a hand here, sneaker-covered feet there. The three figures start to move as the soundtrack quickens in pace, switching from Native Deen to Brother Ali’s ‘Tight Rope’.

And for several energetic minutes, the three abaya-clad figures work their magic.

Sounds like no dance performance you’ve ever seen, right?

It’s called ‘We’re Muslim, Don’t Panic’, and it has been performed in a place many would consider unlikely: all over Minneapolis, Minnesota in the US Midwest.

The work was choreographed by dancer, teacher and artist Amirah Sackett, who is chatting to me over Skype as she waits for her friend to give birth in a hospital in Minneapolis.

For Amirah, putting together pieces such as ‘We’re Muslim, Don’t Panic’ is a way to connect young people, as well as to connect with young people.

It’s also a personal expression of two things she holds dear to her heart – her faith and hip-hop.

‘I’ve seen this great thing happen especially with school-aged kids,’ she explains.

‘Muslim kids feel proud to be represented that way. It’s cool because it’s hip-hop, and being American and Muslim, hip-hop is part of their world.’

Amirah is older than the two young women who perform with her in ‘We’re Muslim, Don’t Panic’. When the piece was conceptualised and shot, dancers Khadijah Sifterllah-Griffin and Iman Sifterllah-Griffin were in their early teens.

As their dance instructor, Amirah remembers a time when hip-hop wasn’t mocked or denounced for its misogyny, violence and glorification of criminal pursuits.

‘I grew up with real hip-hop – the old hip-hop, the kind that wasn’t about sex, drugs, or haram things,’ she says.

Accordingly, her performance is the farthest thing from a lascivious work you could think of.

The abayas worn by Amirah and her two students during the performance enshroud their figures, enveloping any possible physical curves in a sea of black.

‘It’s not suggestive at all,’ she says.

For the three performers, this choice of outfit affirms Islam’s frowning on the reduction of a woman’s worth to her aesthetic value, but it also reflects the cultural legacy of their chosen dance and music genre.

‘By choosing baggy clothing we’re sending the message that we don’t want to be objectified,’ Amirah says.

‘In a way they’re changing the way they dress to show their skills, not their bodies.’

The setting of the piece is black, like the girls’ abayas and niqabs.

In fact, the only visible parts of the girls’ moving bodies are their hands and eyes – and in their fast, coordinated movements against the pounding soundtrack of Brother Ali and Native Deen, the audience detects energy and life.

It’s gripping stuff; Amirah is clearly proud of her two protégés.

‘They came into one of my classes and I was so excited to recruit them – they’re so young, they love dancing and hip-hop and they’re good Muslim girls,’ she says.

‘Real hip-hop dancing is about attaining skills and achieving things that are physically difficult, so it’s almost like we view it more as a sport or skill building thing.’

Amirah came from a fitness and dance background and was keenly aware of an already existing gender imbalance in her field.

‘In the hip-hop dance industry as a woman you’re already fighting stereotypes, whether you’re Muslim or not,’ she says.

‘When you’re a woman and you’re popping or breakdancing you’re punching stereotypes, so as a Muslim woman you’re dealing with stereotypes within stereotypes.’

Amirah’s unique way of exploring personal identity through combining Islam, hip-hop and dance can be read as a consequence of life as a Muslim minority – where religious practice and observance can be explained to a doubting, fearful non-Muslim majority, using language that speaks to them.

‘Non-Muslims when they see the video portion, they understand what hijab is,’ she says.

‘That was part of my goal – to educate non-Muslims and to tell them about hijabs. It [the performance] introduces this image to non-Muslims about something they’re afraid of.’

Having performed ‘We’re Muslim, Don’t Panic’ several times, the trio have encountered a range of responses to the piece.

‘A little boy at a middle school said he hadn’t talked to any Muslims before seeing us dance,’ Amirah explains.

‘After he saw a performance he asked to learn how to do that! I think it made a bridge between us, and he actually thought all Muslims dance like that.’

She says that before and after she came up with the work, she ‘really prayed a lot about it’.

‘I went with the feeling inside me which was to do this because it helped build those bridges. It’s opened a lot of conversations with non-Muslims.’

However, in a more conservative Muslim societal context, Amirah’s art would be framed in terms of its permissibility, or its perceived ‘haram-ness’ or non-permissibility.

Yet it’s possible to describe the activities that she teaches and practises in terms of the benefits they bring.

Hip-hop dance and performance art ‘keeps kids out of trouble, are a form of expression [for them], and it’s something I love.’

‘I don’t want to end up like France,’ she says, referring to a country in which Islam is the second-most widely practised faith, but where rampant discrimination and poverty have affected the lives of French Muslim youth, culminating in riots in 2005 widely covered by the world’s media.

‘For the most part it’s received really well by Muslims and non-Muslims,’ she adds.

‘Various conservative viewpoints might not agree, but it’s where we are at here in the US. For this community, it works.’

View more performances at Amirah’s YouTube page

This article originally appeared in the May 2013 Arts issue of Aquila Style magazine. For a superior and interactive reading experience, you can get the entire issue, free of charge, on your iPad or iPhone at the Apple Newsstand, or on your Android tablet or smartphone at Google Play