Steadfast in her beliefs, she vowed to put her nation first – even before her own family. Jack McGee takes a look back on the life of the former prime minister of Pakistan on the anniversary of her assassination.

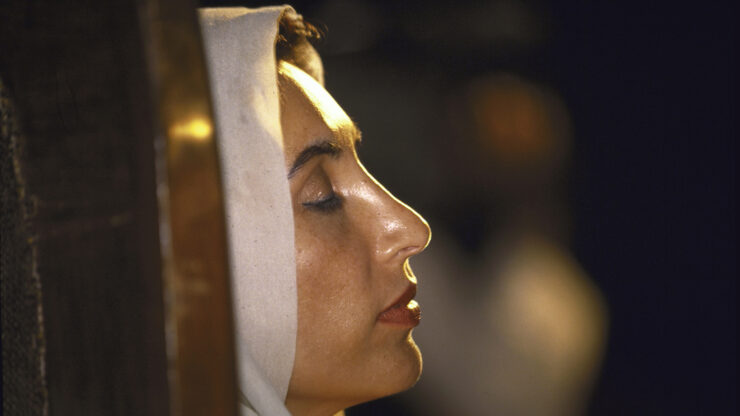

She is often lambasted as having been un-Islamic, corrupt and out of touch with the people. Such criticism is all very convenient in hindsight, but there is little doubt that Benazir Bhutto represented the hopes and dreams of millions around the world. At home she vowed to represent the voice of the poor; abroad she was seen as a voice of reason in a sea of chauvinism, paving the way for women’s rights in Pakistan. Although she may not have achieved everything she is said to have set out to accomplish, her impact was legendary.

To even begin to regard Benazir as more than another politician is to acknowledge the special position she faced when entering politics. Long has she been judged by her faults, measured sharply against any gains. After all, a woman in politics is expected to be perfect and without smirch, able to express herself on behalf of her entire gender. If we cannot help judging her by her failures from the luxury of our democratic homelands, we cannot begin to imagine the milieu of entrenched bigotry that faced her when she took power.

Born in 1953, just six years after the creation of Pakistan, Benazir was the eldest of four children. Hers was a family of wealth and fame, far removed from the misery and poverty of the Pakistani masses of the day. Her grandfather was one of the highest-ranking politicians under the British Raj, and her father was the foreign minister at the time of her birth.

But a level of prestige and opportunity exists for nearly all prominent politicians in the country, even more so during the time of her ascent. Money buys education, and education emboldens. To judge whether Benazir was a good servant of the people she chose to represent, we need to look beyond her faith, overseas education, and lifestyle. Her choice of translucent Hermès scarves worn as dupatta (headscarf) may have been too much for some, but she never claimed to represent anything but the most moderate form of Islam.

She identified with the early heyday of Islamic culture, a period of discovery and intellectual curiosity.

As a Muslim, she identified with the early heyday of Islamic culture, a period of discovery and intellectual curiosity. For Benazir, the brilliance of the accomplishments of Muslims during the Dark Ages of Europe in areas such as medicine, science, thought and art had been dimmed by the sectarian violence that has existed for centuries.

In this regard she felt that however great the achievements of the Moghul and Ottoman eras had been, Muslim pride in our times was rarely derived from economic innovation or intellectual creativity. Rather it had become, and still is, increasingly caught in a negative outlook, plagued by internal sectarian misunderstandings and a defensive attitude of repelling ‘Western assaults’.

This destructive thinking had allowed extremists to fuel the idea of a clash of civilizations between East and West, feeding anger that detracts from the internal causes of decay. She called upon Muslims to speak out against not only assault from the West, but also Muslim-on-Muslim violence, even when it was not politically convenient. ‘It is so much easier to blame others for our problems than to accept responsibility ourselves,’ she wrote in Reconciliation, completed just days before her death.

In 1969 after completing secondary school in Pakistan, she was sent to the United States to study at Harvard. It was the height of the Vietnam War. She saw firsthand the power of the people; that they could change policy and even bring down the government. Internationally, it was a major period in the development of equal rights for women. This was her first exposure to an environment in which women were starting to be treated as full participants in society. It could not help but thoroughly shape her political being. She was the first woman in her family not to wear the burqa; her father told her that it was no longer necessary.

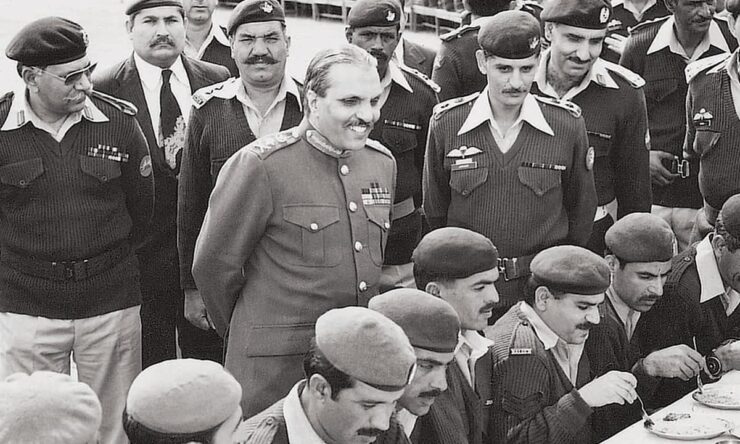

Her biggest opponents always remained the Pakistani Army. This was an increasingly conservative band of men who used their interpretation of religion to defend their chauvinism and drew upon threats from overseas to bolster their military muscle. During her time at college, her father was elected president of Pakistan. In 1977, just after she had finished studying at Oxford, the head of the army, General Zia, staged a coup and imprisoned Benazir’s father, sentencing him to death. She would visit him in prison, and it was during that period that she had deep conversations with her father about leadership and representing the people. Her level of involvement in politics increased when her father asked her to take over. In a traditional Muslim family, this responsibility would have been expected of the eldest son. Her father gave it to the eldest child, and the one in the best position.

But Benazir, and indeed her entire family, paid dearly for their political beliefs. She was convicted on trumped-up charges shortly before her father’s execution in 1979. The next five years saw her alone in sweltering prison cells or under house arrest. In 1984, mounting international pressure forced General Zia to release her into exile for medical reasons. The following year, her brother Shahnawaz was killed in France under murky circumstances. More than a decade later a police shootout, considered an assassination by many, took her brother Murtaza.

In spite of the deaths, Benazir persevered. Drawing on the popularity of her late father, she no doubts enjoyed a certain aura. Seemingly overnight another charismatic Bhutto had appeared, representing a democratic and progressive Pakistan. Everywhere she went she roused a huge crowd, each more passionate than the one before. At that time she could have rallied the masses to take down the government. But she believed in the sanctity of the vote and the power of the voice over the bullet. She echoed her father’s call that there should not be bloodshed or violence.

In 1988, an unexplained plane crash killed General Zia, allowing Benazir to stand for election. The people of Pakistan responded, electing her as prime minister. At the age of 35, she was not only the youngest PM of a majority Muslim nation but also the first female one.

On her first day in office, she freed political prisoners and removed censorship. After a decade of repression and dictatorship, things started to change. To the villages, she brought water and electricity. To her nation, she brought international news broadcasters and the cell phone. She had 48,000 primary and secondary schools built. She believed that in the face of the murderers and torturers, democracy was the greatest revenge.

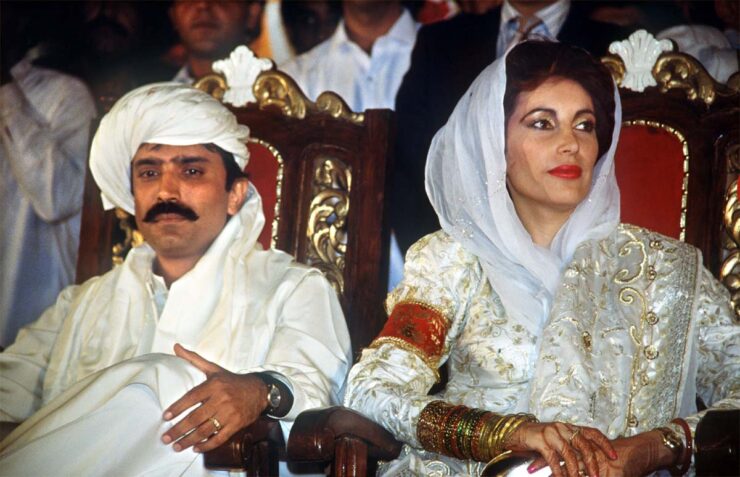

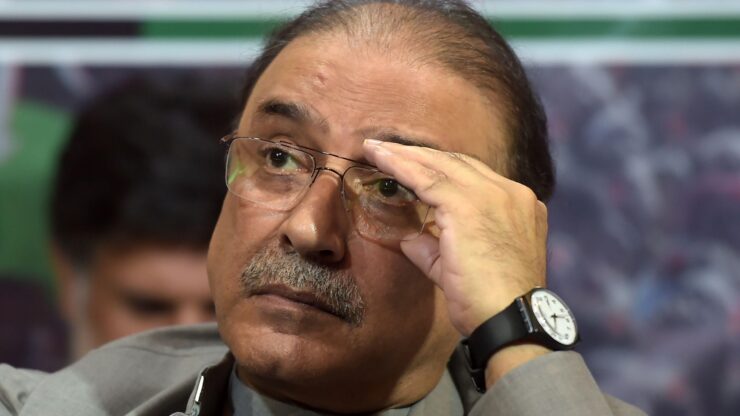

Her two terms in office were both interrupted by allegations of corruption. Asif Ali Zardari, her husband and current president of Pakistan, became known as ‘Mr. Ten Percent’ for the allegedly corrupt deals he cut while serving in his wife’s governments. She was asked to account for money found outside the country, and she often had to spend time in exile in London and Dubai when not in power. But she never gave up on her dreams for the nation, no matter the cost.

On the night of her assassination on December 27th, 2007, she was prepared for the worst. She’d left her daughters with their father in Dubai after discussing with her family the high possibility of never seeing them again. Her fears were realized.

We cannot disassociate her from her family. She had a choice whether to enter politics, and we cannot deny her this privilege and choice simply because of her wealth. The trouble with Benazir was that everyone pinned their hopes on her as being the coming of a savior, rather than conceding that she was only one face amidst a whole situation in need of fundamental reform. History has shown that if you create an idol, she will fall. But if you look at the intention, it can overcome all the failures.

This article originally appeared in the December 2012 Holiday, Celebrate issue of Aquila Style magazine.