Founder of a Kashmiri organization helping to care for women’s psychological wellbeing, Justine Hardy continually fights to raise awareness of the effects of violence on mental health.

This article first appeared on Women’s Voices Now

There is one question that comes up again and again in the lectures I give on the psychological effects of war on mental health.

“Are you sure this kind of mental trauma really exists?”

Over and over it is asked, during the Q&A part of talks and lectures. The questioner usually looks me straight in the eye as though, by holding my gaze for long enough, maybe they can make me crack under the pressure and admit that it is all made up – a touchy-feely notion fabricated by psychiatrists and therapists. Whether the question is asked in public or in private, I have learned to reply in a way that I believe is honest, though probably not very comfortable for the questioner.

“You’re obviously lucky enough not to have experienced conflict, otherwise you would not ask the question.”

There is no doubt about the psychological effects of violence, whether manmade or caused by natural disasters. The mental damage caused by the war has been given many different names over time. More than 2,500 years ago, the Greek historian Herodotus described an Athenian warrior, “struck down without blow of sword or dart”, as he fell dead in front of Herodotus in the middle of a battle. During the First World War, it was termed “shell shock” and then “battle fatigue”, “combat exhaustion” and “war stress” in the Second World War. Now it has a more generic name, Post Traumatic Stress Disorder, a term that has left the confines of conventional war and is applied now across the divide between soldier and civilian – and not just to men, but to women and children as well.

“Women and children?” A doubting questioner will sometimes ask. “Are you sure? They’re not on the frontline, why should they be affected?”

It would be too cheap to say, “Ah, so you admit that the frontline does affect people?” But there is no point with those who have set their metaphorical jaw against the idea of this kind of mental suffering. The point does not need to be argued, it can simply be illustrated.

Modern wars produce images that imprint themselves on our psyches. These come to symbolize everything about a particular conflict, marking the shift of the frontline from those once conventional trenches and battlegrounds, into our cities, onto our streets, and into our homes.

There is a particular kind of photograph that has been seen in many variations, depicting stories across the warzones of the world. Each version is of a woman at the feet of a man in military fatigues. The woman’s body is collapsed, submissive, her face lifted to the man, her mouth wide, the sinews of her neck taut, her hands raised, imploring, begging. The man stands above, weapon raised, safety catches off, utterly powerful, and empowered by the ability to take away the life of she who gives it.

In conflict, every fiber of a mother’s sense of being shudders into protective overdrive. She will push herself across her limits in order to defend her family and to keep her men and children away from the fighting. This instinct knits societies together while so many of the other structures of civil and civic order collapse. While the men are away families continue to be fed, children are educated, aging parents are watched over, prayers are offered, rituals observed. But when the women of society are reduced to begging for the lives of their children, on their knees, at the nozzle of a gun, the society begins to break down. In violent times, the mind mirrors society – it too shatters.

“It hurts so much,” said a young woman to me recently at our mental health program in Kashmir, North India, a region that has been going through violent conflict and upheaval for more than 20 years. She was one of the students in our training course. They had been watching a series of media images taken across those 23 years and across the arc of this conflict that began in 1989. These are not pretty pictures, and there had been no censorship of the cruel images of the wounded and broken bodies of men at war.

But it was not the ones of the dead and dying fighting men that were too much for the young woman. It was a picture of a woman, barefoot in a threadbare salwar kameez, a tunic and lose cotton trousers, on her knees, begging at the end of a gun barrel, her face twisted in pain and supplication.

“This is too much, too many memories for me. Can we ever recover from this?” the young woman asked.

Yes is the answer, you can. We can, because of the shape of life, the passing of time, the slow genius of nature, draws together both the physical, ragged edges of wounds and with more time, the raw mental fractures as well.

The nature of the mind is genius. The tiny fraction that we know of its workings gives us barely even a glimpse of its full capabilities. We are very untrusting of its methods to heal itself in the aftermath of extremes, whether the damage or the mind-bruising has been caused by internal or external violence. By “internal or external” I mean whether the psychological damage is as a result of something external, such as living through the constant violence of a war, or as a result of an internal emotional pressure cooker building to the point of explosion, years of anxieties crashing into each other to the point of mental breakdown.

It is at this point that we are very quick to medicate, to shut down the terrifying symptoms of mental breakdown by creating chemical changes in the brain. It is a valid response, but there is a strong and growing argument for reassessing the use of medication, and for using it as a short term response that will allow the brain to return to a more balanced state, a place where the real healing work can begin, rather than as a singular long-term solution.

One of the most powerful foundations of this idea of psychological healing is for each of us to understand how our own mind works. In this process, we examine how our habit patterns were formed, which ones are useful and which are either outdated or destructive to us. From this microcosm of our own mental world, we then apply this understanding to the world beyond us, and to the real balance of the human condition, in all its creativity and destructiveness.

Cynical questioners may challenge whether violence and conflict cause long-term mental trauma and breakdown, but they pose their questions from a place of ignorance. Theirs is a denial of the harsh truth that within this balance of the human condition, we desire wars as much as we long for peace when war is raging around us.

Is it very arrogant to say that, across millennia, women have had to learn to adapt to this balance of creation and destruction faster than men, because they have to carry on with the day-to-day during the war, maintaining the rhythms of life while, across those same millennia while men have waged those wars?

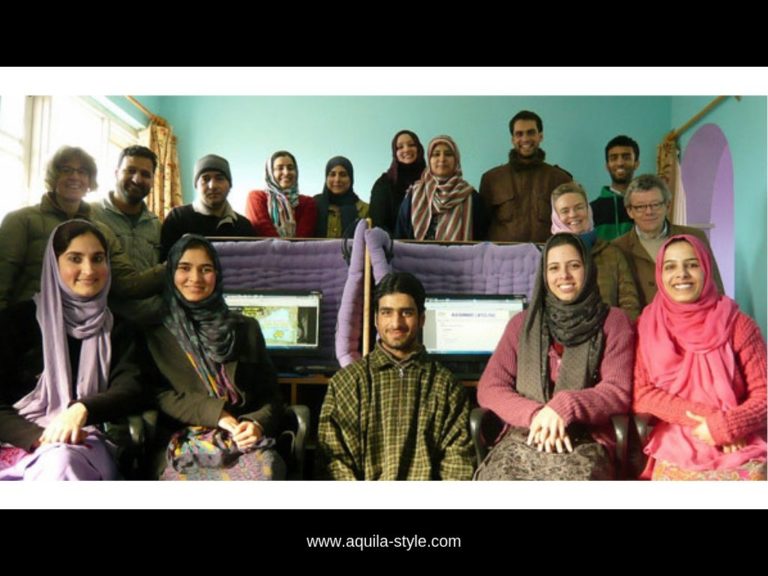

I don’t think it is, which is why the majority of our mental health team in Kashmir are women, addressing their shattered society in the same ways that women have always held their families and communities together during the war.

At Healing Kashmir, we believe that understanding mental illness is essential in overcoming the cultural stigma and dearth of resources that is so characteristic of Kashmir’s mental health crisis. We have created a three-tier system that reflects the way women bind their families together. Women listen: to match this we started the first suicide helpline in the region and trained our team to listen to guide, and support people calling in at that moment when there seems to be no alternative to suicide. Women nurture: we have set up counseling and mental therapy centers across the troubled Kashmir Valley in places where there is little medical care.

In addition to mental health care, we help people get back to work and find out what financial support might be available to them in their area. Women educate other women in times of violence: we have tapped into a national, grassroots rural network of primary child health workers. Over the past year, our small team of 12 has trained a thousand of these rural women as basic mental health care workers, teaching them to support those with low level mental issues, within their villages, and helping them to identify those with more serious problems, so that they can be referred to us for more advanced mental health support.

The young woman who asked the question “Can we ever recover from this?” now leads this rural training program. She has now seen what women can do, and so have I.

Justine Hardy is the founder and a trustee of Healing Kashmir. A writer and therapist, she also serves on the Advisory Board of Women’s Voices Now.

This article originally appeared on The WVoice.